For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

Extracts from 'They Came to Malaya, A Traveller's Anthology', Compiled by J.M. Gullick.

From the section called Ceremonies and Recreations.

80. Sport in the 1890s- The lighter Moments by John Russell on page 259

81. A Night Out by John Russell on page 264

82. Entertaining the Navy by John Russell on page 266

83. Taking the Air by John Russell on page 268

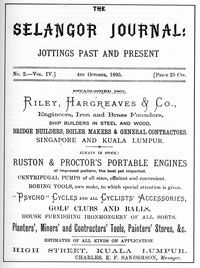

An item in the 'Notes and News' pages of the second number shows that the Journal's committee members lacked neither courage nor confidence:

‘Some kind friends of ours, while lauding the idea of a magazine for Selangor, as an effort in the right direction, have been troubled with great searchings of heart as to whether it will "live." To these we would respectfully make answer, with a proper sense of gratitude for their good opinion of our fosterling, that the question is neither here nor there. The magazine will last while there is work for it to do: when that work is done, it will be no hardship for the editors to stop editing; and the limit of time, whether it be six months or a year, or a series of years, does not greatly fill them with concern.'

Future numbers of the Journal were published regularly every alternate Friday, and contained a fascinating selection of day-to-day news items, together with authentic glimpses of the past.

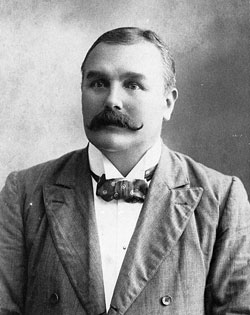

Although many of the news items bear the stamp of John Russell's style, it was not until 2nd December 1892, in the sixth number of' the Journal, that there appeared a complete article written by John, in which he refers to himself as 'the Caxtonian'.

This article is an account of a week-end spent at Dusun Tua, a place renowned for its hot springs where the government had built a rest house for visitors.

The 'child' in the narrative was almost certainly John's eldest son, George Dearie Russell, on the threshold of his fourteenth birthday. The identity of the 'engineer' is unknown, but the fact that he worked in an engineering 'shop' of the P.W.D. would have been enough to endear him to a creatively minded boy of George's age. 'Charles' was undoubtedly Charles Paxon, John's fellow Mason.

SOME ACCOUNT OF A TRIP TO DUSUN TUA.

The great wave of work flowing through the P. W.D. had in its course splashed a few drops into the shop of the Engineer — or, as he might will be termed, the Unconscious One — necessitating a visit to the Rest House at Dusun Tua. To "Charles, his Friend," he suggested the idea of walking there; an idea taken up by Charles with alacrity, who further undertook all arrangements connected with the commissariat. The Child, who acts as Chorus to the Unconscious One, and the Caxtonian were invited to be of the party. The baggage of the intending pedestrians was despatched by bullock cart on the Friday, and at one o'clock on Saturday, the 19th ult. the Caxtonian made his way to the Selangor Club there to meet the Engineer and the Child. Charles was to join the party on the Ampang Road. The elation of the Caxtonian at the prospect of an excursion, the first since his arrival in the State, was somewhat at tempered by doubts as to whether, although he intended to be back at 10 A.M. on Monday, he ought to have had a lot of leave-papers signed before venturing out of Kuala Lumpur: so it was with quite a guilty feeling that he passed the Sikh on guard outside the Government Offices and glanced with dread at the flag flying at the Residency.

The sight of the Child put to flight these thoughts and he gaily stepped into a gharry that was waiting, cheered by the reflection that for nearly 48 hours he would be free from importunities to produce, as a special favour, either wedding-cards or dance programmes, or be called upon to write explanatory minutes with regard to "Errata.” But alas! scarcely had it been decided that the floor was the best place for the three topees, after an ineffectual endeavour to make them pagoda-like occupy the vacant seat, and hardly had the most comfortable arrangement of three pairs of legs been come to in a space barely sufficient for two, when the Unconscious One produced a copy of the Journal, and had read only a few lines when he burst into boisterous mirth. The Caxtonian shivered perceptibly: he tried to think whether there was something really funny in No. 5, but the Engineer gave him little time for thought...'

Here the engineer referred mockingly to a scientific article which had appeared in the previous number of the Journal.

It was useless for the Caxtonian to urge that the scientific gentlemen who wrote the article knew what he was about, and that to alter “copy” would be a breach of faith. The Engineer pooh-poohed this and then proceeded to detect other flaws in the piece, the Caxtonian clearly seeing that the spirit of his holiday had already departed.

At the fourth mile Charles was met and the gharry dismissed, 1.30 P.M. It was then discovered that the Child, in addition to a net and pickle-jar for catching moths, was encumbered with a brown-paper parcel. Imagine a brown-paper parcel and a ten mile jungle walk. The Child explained that the obnoxious bundle contained mosquito-curtain, he having been given to understand that they were short of them at Dusun Tua. Both Charles and the Caxtonian, as Government officials, felt called upon to take up the cudgels on behalf of the institution run by the State, and informed the Child that the Government of Selangor did not do things by halves, and that when it was stated that a Rest House was furnished it could be taken for granted that such was the case. If the Child was not such an irrepressible, unabashable youngster he would have felt that he was thoroughly and properly sat on: but he didn't. He said it would be all right if each did a share of carrying it. The idea was not considered a good one, so the dreadful parcel was left at a Chinese shop about a mile out of Ampang.

The path is fairly well marked and gives few opportunities of going awry. Twice a false move was made: the first time the path taken led to a mine, where a China-man soon put the party on the right track and the second time that the wrong path was taken it so soon became impassable that the mistake was quickly apparent. In some places the path ascends very quickly and unless one is in condition it is a stiff pull. Writing from memory, the worst walking seemed to be between the seventh and ninth miles. Charles, who was suffering for a cold, felt the walk rather trying hereabouts: it was at this point he was heard to offer fabulous sums for a bottle of beer, or a green coconut, or fruit of any kind. It was here that the Engineer seemed quite unconscious of other people's suffering, and plodded on in front, with the Chorus close at his heels and here, too, it may be remarked how gamely the Child stuck to it. It was very necessary that someone should take the lead and force the pace, because the negotiations re getting rid of the brown paper incubus had caused dire loss of a lot of time.

In places the path runs along the edge of valleys that are very deep indeed, and much magnificent timber is seen. At many points of the walk a halt to look about would have well repaid the travellers, but the lateness of the hour and the uncertainty of the road to their destination precluded this. On their way they came up to and passed some of Charles’ coolies: Charles and the Caxtonian eagerly examined the barang-barang of the various coolies to find something drinkable; and when it was discovered that the nearest approach to anything liquid was a tin of salt butter, their disappointment was pitiable.

The longest lane has its turning, and some road metal stacked in cubes and a number of Ranigungee drain-pipes gave notice of the proximity of a village of some sort, and soon the party entered Ulu Langat. The Caxtonian had started with the intention of seeing as much as possible: but he sat down on the first seat he came to in Ulu Langat, and Charles sat beside him, and nought could move them to explore even the high street, when they learnt that the road to Dusun Tua lay in the other direction.

The Engineer was anxious to get on. So leaving Charles and the Child to wait for some green coconuts, he, accompanied by the Caxtonian started off at a good pace on the last portion of the journey. From Ulu Langat to Dusun Tua the road is straight and wide, and when its level is made up to that of the several bridges recently erected, and the metal stone stacked along the roadside has been spread, the Ginting Peras road will be a good one to traverse. In wet weather it must be heavy going. The party, however, were fortunate in this respect, and were able to appreciate the scenery at those points where the river could be seen brawling and tumbling along; at one place, especially, just before arriving at Dusun Tua, the view, looking up the river, arched in by large overhanging trees on each bank, was really beautiful.

A gentleman belonging to the P. W.D. who had walked forward to meet the Engineer led the way to the ferry. A shout of "Kabun!" brought into sight a very cranky sampan: the heart of the Caxtonian, who is exceedingly nervous, sank within him, and he glanced around in vain to discover some other means of reaching the opposite shore. His feelings were not relieved by the nearer approach of the sampan, which proved to be half full of water and leaking dreadfully. Lady visitors, arriving at the Rest House tired and worn out after the walk from Ulu Langat — the road can hardly be used for vehicles — must find this last item an inconvenient and uncomfortable one. The first piles for constructing a bridge are now being driven; it will be a great improvement when the bridge is completed.

No mishap occurred, and the "boat,” wobbling safely across the stream, deposited its passengers on the verge of the Rest House grounds. It was a clear, calm evening, and the beauty of the spot was seen to great advantage. The view from the verandah, though a trifle circumscribed, was very fine: on the left the river, rushing and swirling, gave the place its chief charm; in front, across the lawn, rose the jungle, sombre and dark in the evening light; while on the right could be seen the steam ascending from the hot spring. It gave one an uncanny feeling to watch this steam rising out of the earth, and the impression was not lessened by a nearer inspection. Boulders of grey rock, worn into all kinds of shapes and grooves by the action of the water, stood out in verdureless bareness; and in the hollows and crevices where the water had settled a peculiar-looking deposit, greenish-black and frothy floated on its surface. The almost boiling water, steaming and giving off an unpleasant odour, rushed out of a hole in the side of a kind of sump that has lately been made: and gazing at this tank, in the dim light, with the vapour hovering around it, one could imagine that by clambering up and looking over its edge a glimpse into some infernal region might be had.

Charles and the Child had by this time rejoined the party, which wended its way back to the Rest House. The Engineer had informed the others that he had engaged all four bedrooms: he meant well — but there were only two. There were two bedsteads, and four cane sofas; but only four mattresses and four sheets; no blankets. At this the Child pricked up his ears, and remembering the lesson he had received on the Ampang Road, said there must be a mistake: “If Government said a Rest House was furnished,” etc. This formula he repeated when he discovered that towels were not provided; when a piece of calico with a light check pattern was brought forth to do duty for a table-cloth; when he was told there were no table napkins, and when he had to wait his turn to use a spoon.

But of the merits and demerits of the Bungalow at Dusun Tua, and the return journey, Charles has promised to write in a future number.

True to his promise, Charles wrote 'Home Again' in the seventh issue of the Journal published on Friday, 16th December 1892. He describes how the Caxtonian and the Child erected a bamboo bridge across a stream 'with the ease of experienced junglewallahs', so that he could take a photograph of Dusun Tua before their departure. Charles also comments on the deplorable services at the Rest House.

In the same number of the Journal, John Russell introduced Christmas in 'Notes and News':

A MERRY CHRISTMAS.

It is hard indeed to avoid a feeling that we are only “playing at Christmas" in the tropics. Where is the snow? The thermometer is insultingly high, 90, or more, in the shade. Where are the fur-lined cloaks of the ladies and the hot mulled drinks of the sterner sort? Where is the skating, and the pleasant gathering of old (and young) familiar faces? Where is the Christmas log with its magnetic attraction, after a day of bright ringing frost, and where are the ghost-stories told around it in the uncertain twilight? Where are the holly and the ivy and — the Spinster's friend — the mystic mistletoe bough, cut by antediluvian druids with a golden sickle upon an antediluvian oak? And where, oh! where, are our old friends the Waits? Their absence, surely is "the most unkindest cut of all," and we turn for comfort to our most ancient pipe and the ubiquitous peg — or if we are of the fairer sex to the well-iced lime squash — with a scarcely repressed conviction that Christmas in the tropics is a hollow mockery and a snare — until the time comes to dress for the Fancy Dress Ball!'

Despite John's pretended melancholy, and the absence of ‘Waits’, or carol singers, Christmas in the Kuala Lumpur of 1892 was celebrated with gusto.

The fancy dress event was held at the Selangor Club, and John recorded a full description in the Journal of 30th December. He wrote:

The Fancy Dress Ball, to which we have all been looking forward with much anticipation of enjoyment, may be pronounced to have been a far more brilliant success than that hoped for by even the most sanguine.

Ernest Birch came dressed as a French Guards Officer, while his wife was arrayed as a Cantonese Lady. More than eighty European men and women took part in the fancy dress parade, and the dancing continued until 4 o'clock next morning.

The Birches, who had six offspring of their own, gave a highly successful children's party at the Residency, which was also fully reported.

In this last Journal of 1892, John Russell contributed his own light-hearted ghost story:

MY GHOST.

It was our first Christmas in the East. For some time previously the children had talked of nothing else: I had promised them that the festive season should be observed in due and ancient form. "Roast beef plum-pudding, snapdragons" — I had got as far as this in enumeration of things which to my mind were essential to Christmas, when one of the youngsters said, "And a ghost, father; we ought to have a ghost," “To be sure," said I, "you are right; there ought to be a ghost." My wife observed that if I persisted in the roast beef idea, and allowed the children to eat plenty of it before going to bed, she was confident there would be no lack of ghosts for them during the night. But my wife is so prosaic: she did not agree with me that it was necessary to have a large piece of roast beef for the look for the thing, even if it proved too hard to eat. Happily, any disagreement on the point was averted by a present of a fine turkey on the afternoon of the Christmas Eve.

While the bird, with legs and wings secured, was lying in my office, I regarded it with delight: thoughts flitted through my brain of sending down to the town for more nuts and oranges, in order that I might make my appearance at home in true Christmas style with a turkey under one arm and a bag of fruit under the other, informing the children that I had just been over to Leadenhall Market. However, having been sufficiently long in the East to observe that if only going from one office to another with, say, a couple of minute papers, it is customary to have a peon to carry them, I thought it would hardly comport with my dignity to be seen struggling home under such a load: the temptation therefore was resisted.

On arriving home after office it was evident that coming events were casting their shadows before. The elder boys, with a zeal that I tried to appreciate, had effectually spoiled all the crotons near the house in order to obtain evergreens for decorating the pictures, while the younger ones were making the air redolent with oranges. Now, I have a strong aversion to the smell of oranges: I can eat an orange, and enjoy it, but when I am not partaking I object to the odour. Still, I am a great stickler for playing the game properly; and Christmas without oranges would be no Christmas for me. So, strange as it may seem, the perfume of the oranges and the torn branches of croton were welcome, and made me feel, despite the heat, that it really was Christmas. My eldest boy was evidently imbued with the same feelings; for as a resting-place was found for the last scrap of croton, and as I sank into a long chair exhausted and bathed in perspiration, he said, "Now we ought to all sit around a big fire and tell tales!" My wife almost fainted at the thought; and I could only murmur, “Ah, my dear boy, don't try your poor old father too far." A compromise was effected by my reading "Jarley's Ghost" to the children, and shortly afterwards they were put to bed.

It was evident that my son and I were en rapport about the proper observance of Yuletide, for when my wife suggested that we might shut the doors and retire, I rather astonished her by saying, "Certainly, but first I must have some hot grog." "Hot grog ?"said she, aghast. "Yes, my dear; I've always had hot grog on Christmas Eve, and it's a custom" — "More honoured in the breach than the observance," interrupted my better half. " I should not like to lapse," I continued. So I called for hot water; and if I had asked to have another dinner cooked it could not have caused a greater commotion in the cook-house than did this simple request for a jug of boiling water at 10.30 P.M. At length it came. But many difficulties are encountered when trying to do the thing properly out here. "Now for sugar and lemon," said I. The elder Weller laid down a dictum of "two lumps to the tumbler," but I had to put up with moist sugar; as for lemons, there wasn't even a lime in the house, only oranges, and when I regretted the appearance of the steaming jorum minus the customed slice of lemon, the suggestion that a slice of orange might do was not acted on. With every desire to carry out any idea emanating from that quarter, I felt that this was too much, so finished my grog and went to bed.

I can't say how long I had been sleeping when I awoke with an uneasy, startled feeling. I hadn't been dreaming; my wife was sleeping soundly, undisturbed; but I felt convinced that some strange noise had roused me. I listened intently, but everything was quiet, and, thinking I must have been mistaken, was just dozing off, when an agonising wail broke out on the stillness of the night: not a distant sound, not even outside, but, to my startled fancy, right in my ear. There was no mistake this time. I jumped out of bed like a shot, and in doing so aroused my wife; that she had not heard the sound was evident, for upon my describing it, and saying it sounded to me something like Uncle William's voice (an aged relative, since dead, with whom some difference had existed), I was told not to be ridiculous, and that I must have been very stupid to have had hot grog before going to bed. At this I felt justly indignant, and said that the state of my nerves was such that I contemplated cold grog. However, I went back to bed, but so impressed was I with the idea that the sound came from there that I found myself gazing curiously round the top and corners of the mosquito curtain. While lying trying to account for this disturbing noise, it came again; this time with a muffled, fainter sound, but still very near. I turned to my wife with a hushed "There! that's in the room." Now it is a remarkable thing that my wife and I never agree on the direction of sound: so I was not a bit surprised when she said, "It sounded to me a long way off."

It was useless to endeavour to sleep with this mystery unsolved, so I lit a pipe and had a walk about. A long, painful wail sounding through the house had the effect of bringing my wife out to me in the sitting-room, looking less confident, but still under the impression it came from the outside, while I felt equally sure it was inside. Well, I decided to walk round the house. It was pitch dark and drizzling, I hadn't a lantern and I couldn't take a lamp. I was always ready to plead guilty to a fair share of imagination, but I never knew how vivid it really was until I was walking round the house that night, or rather early morning. "Well," said I, entering the house, after having made its circuit, "this is a pretty how d'do; we shall feel very fit for Christmas. It will be a long time before I forget this one." "Isn't this," asked my wife, "what you call playing the game. I'm sure I heard you promise the boys a ghost." I thought this last remark altogether uncalled for: and said that, according to the poet, this was not the tone to assume "when pain and anguish," etc.

Well, we retired, and if the ghost howled again I didn't hear it: worn-out nature, assisted by grog, was too potent. I slept.

On going outside the next morning my attention was attracted by a Chinese boy tugging away at a string that ran under the house. His efforts to detach it were unavailing, so he proceeded to squeeze himself through a narrow ventilation opening that ran under my bed-room. I was curious, so went to see what he was doing. I hadn't long to wait, for soon I saw him forcing out — the turkey!

Yes; there was "my ghost." The boy the previous night had secured it with a very long line. It had gone under my bed-room, got the string entangled round a pier, round its wings, even round its neck: and when brought out was apparently lifeless. The flooring under the bed was defective, and the bird had struggled to this hole and there delivered its "dying song." It was found just in time to save its life by cutting its head off.

I was relieved in my mind by finding out the cause of the disturbance, and promptly changed the subject when my wife began to slily refer to "Uncle William." "At any rate," said she "I was quite right in saying it was outside.” This, however, has since proved a debatable point, for I still maintain it was inside.

"Now, boys," said I, that Christmas night, "you must all admit that we have, if your mother will allow me to use the expression, “played the game' properly this Christmas?"

"All except the ghost, father," cried Master Sharp shins.

"Oh, we had the ghost," said their mother; "but your father kept that all to himself."

"Yes," added I, reflectively, "it certainly was ‘My Ghost.’ “ CAXTONIAN.

80

Sport in the 1890s—the Lighter Moments

JOHN RUSSELL

Most of the following reports of sporting activities (and also Passages 80-83 below) come from the Selangor Journal, which from 1892 to 1897 was the fortnightly carrier of news and local gossip to the European community of Selangor. Its editor was John Russell, the head of the government printing department whose presses printed the journal. But a number of other officials, including J.H.M. Robson, contributed news items, often anonymously. In 1896 Robson left the government service to found Kuala Lumpur's first newspaper, the Malay Mail; and so the Selangor Journal, replaced by a more frequent purveyor of news, was wound up. It remains nonetheless, as the following passages show, a unique record of the outdoor and indoor amusements of the community for which it was written.

259

Ladies Cricket

AN amusing cricket match was played on the ground near the Lake, on Wednesday afternoon, 20th September [1893], between a team of ladies, captained by Mrs. Gordon, and a team of men under Mr. Dougal. The men had to bowl and field with the left hand, and to bat left-handed (using both hands) with broomsticks. It was a pity that the ladies had had no previous practice, but they all did well… The decisions of one of the umpires were received with much approval—especially from the ladies. It is sad to relate that, notwithstanding the heroic attempts of the ladies and their extraordinary exertions, they suffered defeat…..

One concluding word of advice to the ladies: the grand rule of whist, silence, should also be observed while fielding.

Malay Football

Some three days a week the Bank end of the Parade Ground is used by the Malays as a practice ground for football…At present the players are Malays only. An amusing half hour may be spent in watching them. The natural gravity and dignity of the Malay is easily noticeable. No preliminary horseplay or turning of somersaults as amongst English school-boys can be seen. After a lot of talking, which is shared in equally by all the players, the ball is started. The game reminds one of the descriptions one reads of ladies' football matches in England. The players make apologetic charges and stand around in picturesque attitudes. The full back may be seen stretched at full length smoking a cigarette whilst a mildly fierce battle is being waged near his opponents' goal. Should the ball happen to trickle his way he will come to life and spread himself around gracefully until the tide of conflict has once more rolled back

wards. The costumes worn by the players are very 'chic’. Where Dolah got those nice boots and stockings from must remain a matter for conjecture. Perhaps his long-suffering tuan

would a tale unfold? Joking apart, however, these fellows will soon get into a better style of play and help fill up the ranks in the regular football matches played by Europeans.

Walking

Last week [Mr. Hancock] appeared among us again and announced by hand bill and otherwise that on Friday, the 8th [June 1894] he would walk four miles on the Parade Ground against eight competitors, taking up a fresh man at each half-mile. A wet afternoon, however, prevented this, so that the event was postponed till the Saturday, when Mr. Hancock competed against seven stalwart Sikhs, 'picked men', all up to the standard of Bill Adams' famous heroes, and with the voluntary addition of our athletic Auditor [Mr. Vane] and Mr. Owen. The weather was all that would be desired and the ground fair, though the circuit was rather limited, the walkers having to do eight laps to a mile. Mr. Hancock started with Sikh Wy, who managed to keep up a gentle trot all the time. Sikh Wogy did better, but 'broke' at any time Hancock pressed him. The same may be said of the others till the last, Oh Gourka, came. This man undoubtedly walked well and steadily in advance of Hancock, and only when pressed hard did he at all break. Hancock just captured him on the line.

At this stage Owen started, but after one lap that gentleman clearly showed that the pace was too much for him. Mr. Vane, in his quarter, walked remarkably steadily and well, making the pace, but was also passed, Mr. Hancock coming in swiftly and displaying a wonderful lot of energy at the end of his four miles (32 laps)....

It may interest some to know that Mr. Hancock's record for an hour is 8 miles with 17 sec. to spare. In 1880 he won the Championship of the World, a challenge cup valued [at] £120,

and having won the Championship of England three times in succession….

Athletic Sports

On Saturday, the 14th [October 1892], by the kindness of Mr. Khoo Mah Lek, some athletic sports took place on the grounds adjoining the Selangor Chinese Club. The grounds are rather too small and only allowed a circular course of

100 yards. There was a long list of judges, handicappers, stewards, starters, timekeepers, etc., but most of them being competitors the duties pertaining to their posts were some what neglected. We give below a short account of the various events….

4. Breaking the pot blindfolded—12 competitors. This was a very amusing event, four earthen chatties being suspended from a horizontal bar and each competitor having to walk blindfolded 40 yards and break the chatty with a stick; very few accomplished the feat….

9. Eating biscuits—this was a very amusing competition and was won by Mat bin Brahim, who said afterwards that he

will never enter into another competition of the same kind…..

13. Climbing the greasy pole—this event fell through……

16. Duck-hunt—this event caused great excitement. The river being very swollen and running rapidly the ducks and their pursuers were quickly carried away to the opposite shore. Won by a smart Malay boy, who went up stream a little and allowed himself to be carried by the current to the other bank and there found one of the ducks.

17. Catching the greasy pig—This was rare fun for everybody except the pig, who was frequently under a heavy scrimmage. The winner of this obtained the price, not the pig; and after Mr. Dennis had been consigned to his sack he

was heard giving vent to his disapproval of the proceedings by much grunting.

John Russell, Selangor Journal, Vol. 2, pp. 8-9 (ladies cricket); Vol. 4, p. 110 (Malay footballers); Vol. 2, p. 324 (walking match); Vol. 2, p. 41 (athletic sports).

81.

A Night Out

JOHN RUSSELL

As with the preceding passage, some material here comes from the Selangor Journal. A sulky was a light two-wheeler carriage drawn by a single horse.

After the Ball is Over

AN amusing story is told of two gentlemen travelling between Sungei Ujong and Selangor after the late race meeting [in June 1895]. It appears that these gentlemen left Seremban in a sulky during the small hours of the morning, after dancing vigorously at the Resident's Ball, and being fatigued with their exertions it is presumed they were dozing peacefully on the homeward journey. All went well until they arrived near the Beranang Police Station when, to their horror, they saw a strange beast approaching, looking as if it meant mischief, and having no weapon at hand, they sought safety in flight, followed by the beast, which stuck to them persistently for a couple of miles, though they are said to have done a record. During their run speculation was rife as to the nature of the animal in pursuit; one declared it must be an elephant, and the other thought it a tapir, but both were quite of one mind as to the advisability of getting away from it as quickly as possible. The party reached Semenyih Police Station greatly excited and sought the corporal's assistance to destroy or capture the daring creature who had chased them so persistently. The corporal marshalled his forces and was about to take the field when the pursuer turned up, and, instead of the dangerous animal represented, he proved to be a donkey belonging to one of Kajang's most prominent citizens……..

Among other things [the owner] said 'One must have been to a race meeting in order to mistake the ears of a donkey for the horns of a tapir.' ... The only sufferer is the donkey, whose master declines to keep an animal that goes fooling around at night trying to frighten people; he is to be sent to Seremban, and placed under supervision.

St. Andrew's Night (1894)

One thing we must chronicle, some guileless youth with a pigtail—who ought to have been fighting for his country at this critical juncture in her history, or, better still, have lost his life for her, ere he could have done this thing—got hold of the haggis and cut it up for sandwiches!

John Russell, Selangor journal, Vol. 3, p. 344 (the encounter with the donkey) and p. 103 (the massacre of the haggis)

82 Entertaining the Navy

JOHN RUSSELL

The Royal Navy had a number of small vessels on patrol in the Straits, to 'show the flag' and, if necessary, chase pirates. HMS Mercury was larger than most, a cruiser of 3, 730 tons and 13 guns; 'when new, the fastest warship afloat'. Her arrival at the mouth of the Klang River in June 1895 was a major event in the Kuala Lumpur social calendar. Parties of officers and ratings were brought up to Kuala Lumpur by train and accommodated in a vacant hospital ward. In addition to the entertainments here described, they took part in a shooting match, a cricket match, and several football matches against local teams, and there were lunches and dinners at the Residency and on board the ship.

The opening paragraph refers to the arrival of members of the Malay royal dynasty, brought up from Kuala Langat in the government launch to join in the fun. The half-jocular but always complimentary reporting of local musical performances was a reflection of the fact that the reporter had to live in the same small local society as the performers.

RAJAS Kahar, Yusuf and several others, however, gladly availed themselves of the opportunity, and the Esmeralda returned with them to Kuala Klang, where the Rajas were most hospitably received by Lieut. Pearson on board the Mercury, and spent a great part of the afternoon in going completely round the vessel, in whose appointments they shewed the keenest interest. The torpedoes, engine room, quick-firing guns, the tanks for condensing water and the luxury of the Captain's cabin alike attracted their attention, and, at length, Raja Kahar paused, and turning round, remarked in Malay, 'This vessel was never built by human agency!' a remark which was duly translated for the benefit of the hosts……

The Cigarette Smoking Concert on the night of the 18th [June 1895], organised by Mr. A. S. Baxendale, gave a very enjoyable evening to a large audience. Had it not been for the kindness of Mr. Tearle, who gave a general invitation to the men to attend a Smoking Concert at his quarters, the room would have been inconveniently crowded. A number of the sailors, however, attended both. Towards the close of the printed programme ... some songs and step-dancing by members of the ship's company were introduced. Unfortunately, there was no one present who could accompany the dances—a great drawback… Mrs. Haines and Mrs. Travers gave a very charming rendering of the duet 'Greetings'. Mr. Dougal is as great a favourite as ever with a Kuala Lumpur audience, he sang 'Sweet Marie' with great expression and taste, and was awarded an encore. Mrs. Haines is always a strong line on a concert programme and her singing of

' Whisper and I shall hear' was much appreciated by her audience, and 'My Dearest Heart' was given by her in answer to repeated applause……

On Wednesday morning the members of the Selangor Hunt Club arranged a meet for the entertainment of their friends from the Mercury, the notice said 'Corner of Maxwell Road, 6 a.m.'. Sharp at that hour a strong party mustered with guns and were soon posted by the Master, who proceeded to draw the jungle near Mr. Paxton’s garden for pig— unfortunately, they were not at home. A move was then made towards the Selangor Coffee Estate, where Mr. Hampshire is living, and here the dogs put out two kijang [barking deer] which were bowled over in grand style, right and left, by Mr. W. D. Scott, the shootist being pardonably proud of his excellent marksmanship. No time was lost in getting the dogs to work again, and very soon they were in full cry after pig, one attempted to cross the railway but was brought down by a clinking shot from Mr. Youel RN, another was fired at and missed. There were any quantity of pig on foot, but owing to the very dry weather the dogs had great difficulty in following up their game. An unfortunate accident happened to one of the best dogs, his foot being terribly bitten by an enormous iguana; this brute was shot by the dog-boy and measured over five feet. By 11 a.m. our visitors were about tired of the sun, and a move was made to the 'Spotted Dog' for refreshments: the result of the morning's sport was sent on board the Mercury by midday train.

John Russell, 'HMS Mercury at the Kuala', Selangor Journal, Vol. 3, pp. 334-42.

83

Taking the Air

JOHN RUSSELL

The lavish use of domestic staff as here described, was possible only so long as wages (typically Malayan $8-10 per month at this time) were low. By the 1930s wages had increased three-or fourfold and the household staff had fallen to a mere half dozen, including a driver and a gardener.

The Straits Settlements had been an Indian dependency until 1867 and Indian words, such as ayah (for a nursemaid) had not yet been replaced by amah (a Chinese female domestic).

Perambulation

THE dusky nursemaid of the East, or of Kuala Lumpar, at any rate, is rather better off than her fairer sister of suburban London when taking her charge out for an airing. (We use the singular advisedly, because in the same way that a syce declines to look after two ponies, so does an ayah declare it impossible to attend to more than one child)…. The ayah is provided with a companion in the shape of a young man, whose duty it is to wheel the carriage. Why this should be, it is hard to say. …..We must suppose that the necessity arises for a young man to assist the nurse in taking one little child out for an hour in the evening, in the same way that the cook here finds it necessary to have a young man to carry home the purchases from the market, to light the fire, to prepare the vegetables, to—in fact, do almost all the work while he smokes—the necessity of doing as little real work as possible. It is the same all round. The house boy would faint if told to wash plates or fetch water, and one gets quite diffident about asking the 'tukang kabun' [gardener] to run with a message.

John Russell, Selangor Journal, Vol. 1, p. 35 (nursemaids)