For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

John Drysdale had joined the company in 1930. J.A. Russell and Co. was built on borrowed money, the financial position was desperate in the early 1930s J.D. later told Tristan that when he joined the Company he was shocked to find it owed about 9 million dollars. J.D., an engineer, managed Malayan Collieries, the Borneo Colliery, Sungei Tua Rubber, the Kedah Tungsten Mine and the Celebes Panielota Goldmine. He had been instrumental in developing the plywood works , distillation plant and brick works at the Colliery. He and Robbie were also to develop the contacts needed for the Cement Factory. When Archie died J.D. moved from being assistant manager to manager, and Robbie's No. 2. When Robbie was away J.D. acted as his alternate.

J. H. Clarkson joined the Company in 1932. Clarkson, a tea planter, had joined a boat at Ceylon bound for the U.K. and Archie had engaged him then. He worked on Boh but was stationed at Sungei Tua. After Archie's death Clarkson became estate manager.

Alun Llewellyn joined the Company in June 1934 as mine manager. When John Drysdale took over from Robbie, Alun became his No. 2 and when William Gemmell died Alun became Chairman. Tristan Russell would eventually take over from him.

J. A. Russell and Co. Ltd. 1933 - 1942. Who was in charge after Archie died?

Archie had wanted his businesses to continue. He said to his executors : "I express the hope that they will continue the said businesses as going concerns in the same manner as I have done in my lifetime and I declare that in continuing the said businesses my Trustees may generally act in relation thereto as if they were the absolute owners thereof without being liable or responsible for any loss arising thereby and in case such businesses shall at any time be carried on at a loss my Trustees shall be reimbursed out of my estate to the extent of any loss incurred by them in so carrying on the same."

Kathleen returned to the U.K. with Tristan. Money was very short and she had to live on a very small allowance. But she was determined to keep the business going and enrolled on a business course. Her lecturer advised her that when J.A.R. & Co. was converted from a partnership to a limited liability company, she must obtain a governing share. This was written into the articles of J. A. Russell & Co. Ltd. and in subsequent years proved vital in ensuring control of the Company. In mid December 1934 J. A. Russell and Co. became a limited company, holding their first meeting on 18 December.

On 28 March 1935 the company's debt to the bank was $5,679, 108.63. H.H. Robbins was keen to sell assets and many were sold including the house at 2 Syers Road, (24, Jalan Tunku). Kathleen stopped him selling Boh and when she later married William Gemmill he lent a strong hand to control the policy making in J. A. Russell & Co. Ltd. Gemmill eventually became chairman of the Company and remained so until the time of his death. He played a decisive role in rehabilitation of the business after the Japanese occupation.

Don Russell managed the merchant businesses in Hong Kong, Canton Shanghai and Tientsin,(now Tianjin.) As the remaining partner he found that J. A. Russell & Co. was indebted to the bank for very large amounts of stock and property. As his son Mike Russell explained:" J.A.’s executors set up a Trust for the benefit of his wife Kathleen and very young son Tristan, and Archie's brother Don was a Trustee of this for many years. However in his will J.A. had not actually stated that his assets could be kept in non-trustee stock. With Malaya being a British colony then, British Trust laws had to be followed and these were very strict as to what constituted trustee and non-trustee stock in those days. The Court in Kuala Lumpur ruled that only the business of J.A.R. & Co. could be put in Trust and that all J.A.’s holdings in the other businesses had to be sold off."

Don wrote: " At that time any such sale was quite impossible since owing to the world-wide slump it was almost impossible to give the businesses away. A forced sale would have meant having to meet a huge deficit, which, if transferred to J.A.R. & Co. K.L. would have crippled, if not bankrupted them. It was therefore arranged after much discussion that I would take over the merchant businesses". The Shanghai office was closed in 1933 and using a loan Don took over Loxleys in London, Loxleys in China and Perrin Cooper in Tienstin, keeping control of all the shares. The records for Perrin Cooper show that it was incorporated on 30 November 1934, while Loxleys, London was floated as a private company in 1935. He was able to pay the interest on the loans and reduce them, using the profits of these businesses and from dividends in his 25% share in J. A. Russell & Co. Ltd.

J. A. Russell and Co. had been a partnership. In his will Archie had written:" Whereas I carry on business in partnership with my brother the said Donald Oscar Russell in London and Kuala Lumpur and other places abroad under the styles or firm names of J. A. Russell and Company, W. R. Loxley and Company and Perrin Cooper and Company or one or more of them and our respective interests in the said business are seventy five (75) per cent. and twenty five (25) per cent."

His four executors were his wife Kathleen, H.H. Robbins, his brother Don and Andrew Beattie who were instructed to put his assets into a trust fund.

The trust was to be divided into ten equal parts, one for his brother Bob, two for H.H. Robbins the remaining seven for Kathleen.

Archie's known business interests at the time of his death.

Mining: Malayan Collieries, and the closed Borneo Colliery with the subsidiary industries of plywood, wood distillation, manufacture of bricks and tiles, and the well developed plans for cement manufacture. The wolfram mine: Sintok Mines at Kedah, Bakau Tin in Pahang and The Netherlands Indies Commercial Agricultural & Mining Co. Ltd., ( which may have been the company that explored the Gold mine at Panielota in the Celebes,) and The Taik Hing Kongsi near Rawang with Ho Man.

Real Estate: His own house: 24, Jalan Tunku, the bungalow at 147, Ampang Road lived in by Mr. Robbins, and at least 12 plots of land in K. L. which included an area called Kampong Malacca and a vacant lot at Batu Road. In Ipoh an estate of 260 shop houses, the Isis and Choong Wah Cinemas, and five pieces of vacant land, one of which was used for an amusement park. Houses in Seremban.

Planting: Boh Plantations. Rubber estates: These were Sungei Tua Estate at Batu Caves; The Russell Estate at Tenang; Bukit Bisa Estate in Kajang.

Investments: Shares in Malayan Collieries, tin and rubber estates including Kamasan Estate, Amalgamated Malay, New Serandah, and Utan Simpan. Also considerable shares in Selangor Coconuts.

Insurance Agencies: for Royal Exchange Assurance Corp and Queensland Insurance

Associated Firms: W. R. Loxley & Co. in Singapore, Hongkong, Shanghai, Canton and London. Perrin Cooper & Co. in Shanghai and Tientsin, (Tianjin), the financial control of the North China Wool Co., of Tientsin and the Loxley Wool Co., (Pty). Ltd., of Cape Province, South Africa.

1933.

Robbie attended Archie's funeral at Bidari cemetery on the morning of 8 April. The Collieries issued a circular about his death to shareholders on 18 April assuring them that " It was Mr. Russell’s invariable practice to discuss very fully all matters of current and future policy with his colleagues. This, and the long association which all members of the board have had with him, will be of great help to us in continuing the guidance of the destinies of your company"

On 15 May Kathleen and Tristan left for the U. K., and on 25 May H. H. Robbins and his wife went home, leaving John Drysdale in charge. In September at Bakau Tin's A.G.M. Bob was co-opted to replace Archie on the board. On 26 October at United Engineers A.G.M. Robbie agreed to fill the vacancy on the Board which had been given to Archie. In December Malayan Collieries, in a deal with F.M.S. Railways, secured the contract to supply Batu Arang coal to the St. James’ Power station, Singapore, for the year 1934.

A Visit to Boh

In May the Straits Times Planting Correspondent described a visit to Boh writing " Proceeding down the Boh valley one is surprised to find oneself walking on a 12-foot motor road and to learn that between four and five miles of this road have been finished for some months and that only conversion of the bridle path through the intervening jungle is necessary to connect this road with the main Government Road from Tapah. In fact one sees here five miles of a well-graded road over which no car or lorry has ever travelled. After walking one mile one reaches the estate office, ... Here my host, Mr. J. H. Clarkson, met me and we went to his bungalow, built originally by Mr. A. B. Milne with timber felled on the estate. " The site for the tea factory had been cleared and levelled.

Malayan Collieries

In 1934 there were signs of recovery from the slump. The Colliery advertised their MalAply plywood chests heavily all year and the factory making them was featured in a whole page photographic spread in the Straits Times in February. In June the Malay Mail covered a visit to the collieries as part of their “Exhibition Supplement” and it may be at this time that the Collieries produced their detailed "Guide for Visitors", which can be read here.

From the EXHIBITION SUPPLEMENT: THE MALAY MAIL, SATURDAY, JUNE 2, 1934

"PLYWOOD A FACTORY WORKING 24 HOURS A DAY.. A rapidly growing proportion of Malaya’s rubber is being packed in Malayan-made plywood chests, and so many are wanted just now that a 24 hour day is not long enough, and I was told that orders are being reluctantly refused where immediate delivery is required. Here I saw the most fascinating of machines in operation. A five-foot length of timber fresh from the jungle and straight from the pit where it is steamed to soften it, was clamped in position on a ponderous lathe. Upon revolving against a keen stationary knife a layer of wood about a sixteenth of an inch in thickness was peeled from the log. It came off in a continuous unbroken piece and a workman taking hold of the end carried it along a table as though it were a length of linoleum. At the limit of the table’s length the piece was broken, and the workman again took hold until layer was piled upon layer and the log, which was originally over three feet in diameter, was reduced to a core of only 7” across. The rest of the log had been resolved into scores of feet of plywood. Further down the long building the plywood was being stacked on wheeled racks ready for the big heating chamber, where it is thoroughly dried. In another spot the sheets were being run through the rolls of a machine which glues the three portions together. They are then piled up and subjected to the clenching embrace of a powerful hydraulic press. Two guillotines were busy cutting the sheets to the required sizes, the keen blades sheering through a score of sheets at a time. In another portion of the building, other machines deal cunningly with strips of metal for the binding strips, bending the edges and punching and cutting them into the required shapes. At the further end of the factory the finished sheets are graded, packed in shooks and loaded straight on to the waiting covered goods wagons to be distributed to all corners of Malaya.

ACID FROM WOOD EXAMPLE OF SILENT EFFICIENCY One might arrive at the Wood Distillation Plant just across the way from Plywood with a brain that had about reached the saturation stage. But interest receives a fillip, for here is a marvel of a different order entirely. When the Plant is in full operation there is no clank of machinery, grinding of cogs, or whirr of wheels. It is a complete change from the restless pulsation of a busy manufactory for here the end is accomplished silently. Perched on a 15-foot foundation of masonry underneath which the retorts and furnaces are housed is a veritable maze of piping and tanks. Boiler shaped tanks, square tanks, round tanks, vertical tanks and dome shaped tanks—at least they were all tanks to me until I learned that some of them were stills and some condensers, some of steel, some of copper and some of iron. Then there was metal piping of all diameters running in all directions, twisted into all sorts of shapes and convolutions. The whole was dominated by a lofty metal stack from which the smoke poured. The functions of each part of the plant were patiently and courteously explained—but I was content to marvel without really understanding step by step just how the wonders were achieved. For a miracle it was to me. I had seen 50 tons of hardwood billets piled high in 16 trucks. Four just filled a giant 50- foot retort and there were four of these huge chambers. They were closed with heavy iron doors which were further hermetically sealed with fireclay. Next the furnaces were stoked up and the heat, which is carefully controlled and circulates around the retorts, does the rest. From those solid blocks of timber, there is distilled wood alcohol, disinfectants, wood preservatives of different grades and grey acetate of lime. This last provides the raw material from which acetic acid is made. What is left when the retort is opened is a splendid quality of charcoal which finds a ready market. In the adjacent laboratory an enthusiastic chemist further enlightened one or two of us. Patent investigation and many trials had shown that a combination of tar oils distilled half from Malayan wood and half from Malayan coal made a wood preservative of superlative grade, the toxic or fungicidal qualities of which at least equalled the best imported article. “MALASOL” KEY TO THE WHITE ANT PROBLEM. Right here in Malayan coal and timber is the key to the prevention of the ravages of Malayan white ants and the disintegrating influence on its timbers of damp ground and dry rot. And that is not all, for further experiments have proved that here were the raw materials for the main ingredients of a disinfectant of the creosote class proved to be many times more powerful than pure carbolic acid. In fact those responsible for the immense amount of patient research which has obviously been devoted to the evolution of “Malasol” which this new product has been named, claim that it can be produced in a more highly concentrated form than any disinfectant currently on the market. I have at the back of my mind a statement to the effect that one part of “Malasol” to 800 parts of water would kill typhoid germs in a few seconds. Just imagine a mixture of one in 800 being capable of killing anything with even unlimited time at its disposal for the purpose."

.jpg)

The Collieries Directors' Twentieth annual report contained an aerial photograph of Batu Arang. (Seen left with added labels. The view looks south, the plywood works were north of the area shown.)

The Collieries report recorded that trade was still depressed and sales of coal had decreased further. The East mine and Open Cast 7 were being used. The Borneo colliery continued to be closed. It indicated surplus supplies of coal which, due to its tendency for spontaneous combustion, were being stored underwater in Opencast 8 until it could be sold to the Singapore Power station. The brickworks were idle, the continuous kiln was closed down and the intermittent one used instead for special bricks and tiles. As well as the completion of the distillation works, the tile plant had been erected and trials had taken place. The new pilot sawmill was being completed, and the coal washery worked all year. The plywood works operated full time.

John Drysdale had acted as H.H. Robbins alternate from May 1933, but by the time of the A.G.M. in March 1934 H.H. Robbins had returned. H.H. Robbins addressed the 20th A.G.M. beginning by referring to Archie’s untimely death in the worst month of the slump. In the second half of the year prices for tin and rubber had improved. But tin was still restricted with mines producing 25% of their possible production. He discussed the introduction of oil engines and electric motors replacing steam boilers. Coal sales had exceeded production and stocks were being kept under water. The contract for Singapore power station, which required 3,000 tons a month, would use these stocks up. He covered the subsidiary undertakings, explaining the need for bricks, timber, the sawmill, and the waste used in the distillation plant, and the possible use of land where timber had been felled for agriculture. The proposed cement works would use very large quantities of coal and shale, which was a by product of stripping of coal. Cement was being exported very cheaply by Japan. The Collieries were considering taking a British cement plant built not far away and transferring the plant to Malaya. They had decided not to rebuild alone but to discuss co-operating in arranging to transfer the plant to Malaya.

The labour position was causing anxiety with supply in the balance. He criticised the new Workman’s Compensation Enactment for not covering the dependants of Chinese workman killed in accidents if they were resident in China. The officials at the colliery wished for dependants living in China to be included in the act and Mr. Shearn had been to the Federal Council to make their case. The act had come into operation on October 1st 1933. A case at the collieries was used to illustrate the effect of the act on the labour force. " After an accident occurred a notice was posted up in Chinese, at the instance of the miners employees, which clearly showed that the work people were extremely dissatisfied with that kind of legislation. A free translation was as follows: “We work under dangerous conditions. There are always fatal accidents occurring. For instance, one man met with a fatal accident at the East Mine and three others were injured. The relatives of the deceased claimed compensation and at last received $30 for funeral expenses. This man’s death received no more attention than the death of a cow or a horse. That makes us very grievous.” It may the first time the views of the workforce at Batu Arang had been reproduced in an English language newspaper.

At the end of the year when Batu Arang held its third sports day, the Malay mail printed the names of the Chinese competitors at the colliery, possibly also a first for their names to be in print. Mrs. Llewellyn presented the prizes on this occasion.

Property

Kathleen who was with Tristan in London was reported to be suffering from flu and a poisoned hand in March. She and the other executors of Archie’s Estate appealed in the Ipoh Supreme Court against the Sanitary Board’s valuation of his property there for the year 1933. They argued that the slump was at its worst in the early part of 1933, and large number of Chinese and Indian labourers had been repatriated, houses stood empty and it was impossible to collect rents, 50% were unoccupied and rents had fallen by 50% on those that were. The valuation was kept at only a 20% reduction.

Tea

The Singapore Free Press was critical of the Government for their lack of road building in the Cameron Highlands, pointing out that the pioneers had constructed their own roads and remarking: “The general public of Malaya does not yet appreciate the sacrifices which are being made by the pioneers … or the progress which is being made in the face of considerable difficulties. Like all pioneers they will be appreciated too late”. There was also discussion in the press as to whether the Government would bring in a restriction scheme on tea. At Boh there were anxieties that tea would be restricted and J. A. Russell and Co. wrote to the Secretary to the Resident at Pahang asking for an assurance that no restriction would be placed on their planting their reserve lands with tea. They wanted to plant up all 4,000 acres. The Resident asked them to wait. A Government report on the Highlands included a summary of the developments there. The first manufacture of tea in Boh’s new factory began on 28th July and the first consignment was sold in London during November. It considered that two years would be necessary before the planted areas matured sufficiently to give high quality tea.

In April Bob Russell was re elected onto the board of New Serendah Rubber. He left for Home in May and J. H. Clarkson replaced him on the board of Amalgamated Malay Rubber.

J.A. Russell and Co. became a Limited Company

" J. A. Russell and Co." appear on their notice of the Collieries Dividend No. 55 in September and on their correspondence in that month but by December, on the declaration of the Collieries dividend No. 56 their name had been changed to "J. A. Russell and Co. Limited."

The agreement for Don to take over the merchant businesses of Loxleys and Perrin Cooper was made on 12 December. As the new Company of J. A. Russell and Co. Ltd. they held their first meeting on 18 December. H.H. Robbins went on leave until the following March.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The directors’ report showed an increase in sales of coal. The Borneo Colliery remained closed. The Plywood factory operated all year, making plywood chests and plywood sheets, but the brick works remained closed. The distillation plant operated on and off. Negotiations for the additional timber area continued. The sawmill was erected and wood preservative and disinfectant mixers were installed. The club and sports ground were used and the open-air cinema. In March the 21st meeting was presided over by H.H. Robbins, who began by giving an outline of the history of the company, and of the signs of recovery in the economy. The Workman’s Compensation Act had been amended to include dependants resident in China. The brickworks had been idle due to lack of demand by the building trade. The pilot tile making plant did not obtain consistent results and the superintendent had consulted with experts in the U.K. The plywood department had heavy orders, which were not always possible to meet. The wood distillation plant’s products sold well. The timber business had involved a further extension of the railway and more negotiations on the timber area applied for. Plans for cement works were on hold.

In May H.H. Robbins returned from home leave and Mr. Spall Superintendent of the Plywood Factory and Sawmills was engaged. In July a fire in one of the underground mines killed one of the Chinese workmen and H.H. Robbins, Mr. S. Graydon and Mr. W. Prentice were all asphyxiated. “Mr. Scott, under manager of the mine, made himself sick and warned the others who, equipped with respirators, found and rescued Robbins, Graydon and Prentice who were lying unconscious.” They were taken to hospital in K. L. where they recovered.

In August the Collieries stand at the Agri-Horti show was commented on by the Straits Times. “What a great business has been built up, mainly by the brilliant brain and unflagging energy of the late Mr. “Archie” Russell!” exclaims the writer. The article was accompanied by the aerial picture from the 1934 report and a photograph of Archie. The collieries had won the gold medal for the best display.

Boh Plantations.

J. A. Russell and Co. Ltd. minutes record that the local market was researched and suitable trade names and designs for tea packaging were discussed. Arrangements for labels, trade names, slogans and advertisements “ of a conspicuous and impressive nature in Singapore and London”, were made. In October Masters Ltd. in Singapore were working on suitable designs. The main engine at Boh broke down in August and was replaced by December. The Tiger Tea trademark was registered in August and advertised in September. By the end of the year tea sent to London realised prices which compared favourably with Ceylon Tea. Boh was becoming recognised on the market. Harper Gilfilan and Co. were appointed distributors for Malaya.

In June Boh’s manager Mr. Robert Brown was married in the Cameron Highlands. His was the first European wedding to held there; celebrated with kilts, tartan and bagpipes, it was attended by the “entire local populace” including Mr. A. B. Milne.

In September Mr. C.C. Footner gave a talk on the history of the Cameron Highlands, while various newspaper articles promoted it as a holiday area. A writer who had visited Boh in 1932 said: “I had to tramp a weary five miles over a jungle path to reach Boh Plantations three years ago. Last week I made the journey comfortably in a motor-car.”

In November A.B. Milne was reported to be leaving for Ceylon with his brother. Before he left he said “He saw some areas at Boh Plantations containing better grown tea for its age than anything grown in Ceylon of similar age.”

There was further dissatisfaction with the Government over the lack of extra roads in the Highlands and their failure to promote of the area for agriculture. One letter writer considered the money spent on their experimental station at Tanah Rata was a waste . “There is already a full-sized tea plantation with a large modern factory at Boh, and a properly experienced tea planter is in charge, so why go on throwing public money away.. on an agricultural white elephant?”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Selling Tea. The printed labels for Tiger and Boh arrived from the U.K. in March so local sales went ahead. The first adverts appeared in April and May

The tea was distributed by Harper Gilfillan. On 26 June the Straits Times reported on Boh, after 8 years. “This company, thanks in the beginning to the courage and vision of the late “Archie” Russell (the ablest businessman the F.M.S. has ever known) has made a contribution of very real importance to the economic history of this country.” The article gave a history of the Boh Plantations, from 1929 and a description of the estate. A panoramic photograph was printed on the back page.

Arrangements were made with Little's and Robinsons to sell chests of tea in England with the companies paying for the advertising.

Malayan Collieries.

The Collieries report showed a 23% increase in sales of coal, partly due to improvements in the tin mining industry, because increasing quotas had been allowed under the restriction act. Most of the coal came from the East Mine. Work in Opencast 7 stopped and began between opencasts 5 and 7. Opencast 8 became the main one being used. The Collieries had acquired from Messrs. Sir John Jackson Ltd.: 4 x 30 ton steam locomotives, 30 x 12 cubic yard air tipping waggons, 60 x 6 cubic yard gravity tipping waggons and a 2 1/4 cubic yard electric shovel-dragline combination, which had arrived at Batu Arang early in the year. This appears to have been connected with “the Singapore Naval base contract.” The agreements with the Government over access to timber were concluded successfully. The railway line extension continued into the forest to reach the timber. The Borneo colliery remained closed. The brickworks had remained closed with sales being made from stocks but was being prepared to be restarted. John Drysdale acted for time as alternate for H.H. Robbins. 5 ½ millions square feet of plywood had been made in the plywood factory. The sawmill had prepared some timber, which had been sold in London. Distillation had stopped due to accumulating stocks and progress had been slow in establishing a market. Both the disinfectant was advertised from January to June and the new wood preservative in May and June.

H.H. Robbins presided over the A.G.M. Bob was absent due to illness. He was pleased to be able to report improving conditions. They had lost the contract to supply coal to the Singapore Power station to the Japanese. A small experimental unit had been ordered to utilise local clays. There was a fall in demand for plywood chests due to the baling of rubber for export. But he was pleased to say that they had were of a very good standard, they had had no complaints. The plywood was advertised from January to June. He didn’t predict the outcome of the current year due to the “ International situation… that is obscure and threatening” The Johore Coal syndicate had been formed to see if there was any coal there and boring had taken place since. It seemed unlikely that there would be a workable deposit. The papers later reported that the Collieries had negotiated rights to investigate coal at the Allington Hill Estate, Tapah.

In April John Drysdale read a paper about the Collieries to the Selangor branch of the Engineering Association of Malaya. Seven million tons of coal had been produced from Batu Arang in the last 23 years. He gave a detailed description of how the deep mine was worked and its ventilation system. The colliery was dispatching about 40,000 tons of coal per month. He outlined the many possible uses for coal including: “The use of pulverised fuel for such purposes as cement making has been fully investigated and it has been ascertained that Malayan coal is well suited for the purpose.”

Mr. Spall came back from leave at the start of the year. On 7 June H.H. Robbins visited England on a short trip via aeroplane. On 3 August he returned. It took 11 days to return by air, a journey that had previously taken a month by ship and was so remarkable that it was covered in the news. “A KUALA LUMPUR business man, H.H. Robbins, sits at his desk today hardly able to realise that since June 7, less than two months ago, he has been to England, executed a business deal and come back again. ... Now he may look out of his office window at the muddy river in the sleepy Federal Capital, and try to reconcile the scene with the London memories less than two weeks old. MR. ROBBINS, who is a director of Malayan Collieries Ltd., left Malaya for Europe on K.L.M. on June 7, and was away for 6 weeks. Eleven days were spent on the return air journey, so that he had a full month in England. His verdict is that the expense was repaid from every point of view.” In December he flew on a Quantas plane to Queensland.

In August a severe fire destroyed a large part of Batu Arang included 49 shop houses, and many homes belonging to the Chinese and Tamil workforce. No lives were lost. “ Company representatives, consisting of Messrs. H. H. Robbins, chairman of directors, E. Bellamy, colliery superintendent, H. H. Marnie, civil engineer, and J. H. Tubb, works accountant, inspected the ruins of the village this morning. Mr. Robbins declined to make a statement when approached by Free Press representatives, but a Chinese shopkeeper, when interviewed, said the fire began in the roof of his house. A new mine railway passed close to his kitchen and yesterday afternoon at four o’clock he saw a mine train approaching. The engine was going slowly and smoke was belching from the funnel but he did not see any sparks. Ten minutes after the train passed the roof went up in flames. His kitchen fire was out at the time. He and his friends tried to pull off the burning attap but failed. The next-door shops caught fire and the alarm was raised. No official explanation of the outbreak of the fire has yet been given. This morning an aeroplane zoomed over the razed village taking photographs.” A study of the traffic log later eliminated the possibility of a spark from a locomotive.

Industrial trouble in Singapore in November was followed on 16 November by the colliery workers going on strike, the first strike of several. About 300 underground workers from the East Mine had downed tools on at 8 o’clock lock on Saturday night. The Opencast miners then also stopped working. About 400 marched past the General Office to the power station and turned off the power supply. They then went to the police station carrying axes and sticks and were faced by 5 policemen, who fired directly at the miner’s heads. One was wounded. European employees who attempted to pacify them were met with “aggressive gestures” according to the press, and returned to their bungalows. The local police called for reinforcements from Rawang nine miles away. 150 police arrived an hour later, in cars and lorries, although the lights were back on by the time they arrived. After three arrests were made the police found out that the miners were striking about their terms of employment. During the following day there were no disturbances but groups of strikers assembled by the office and police station. The wounded man was taken to K.L. hospital. The Chinese Consul, Tzu Lin Chu, and the Asst. Protector of Chinese, Mr. Norman Grice visited the mine on Sunday and consulted the labour force to ascertain their grievances. A guard of 100 police stayed at the colliery during negotiations. Like the strikers in Singapore, the miners were discontented with the system of labour contracting. Only 50 returned to work in Opencast 8 by 18 November, and 4,200, virtually the whole labour force, were still on strike. John Drysdale promised an increase in wages and adjustment to working conditions, which the miners refused. They had 14 demands, which included a 50 % increase in wages and the withdrawal of the police, which the company refused. About 170 police were on guard. On the afternoon of the 18th the labour contractors attended the negotiations for the first time, with two representatives from each mining gang. The Singapore Free Press interviewed a representative of the miners who explained that they had had some grievances, which they wanted to present to the management, but had had no opportunity to do so. During a meeting to prepare their appeal two miners had been arrested by the police and the miners, being annoyed, had gone to the power station and switched off the lights. A crowd had followed the police to the station and rescued their two colleagues. When the police came the next day and arrested two men, including the one from the night before all the underground miners stopped work. The Chinese Consul helped the strikers to reduce their demands to 6. These were:” Firstly, an increase of 50 per cent. in wages for all. Secondly eight hours work in open cast mines instead of nine. Thirdly, the abolition of excessive fines for breaking rules and cutting tops. Fourthly the provision of clear underground passages for emergencies. Fifthly, no banishment of workmen because of the strike and a guarantee that no discrimination be made against the strikers’ representatives. Sixthly, the arrested men be freed and the wounded man compensated.” This was rejected by the Collieries. After a long discussion the company said they were prepared to hear the grievances if the men returned to work at 7 a.m. tomorrow and would accept an increase of ten per cent. in wages for coal hewers and five per cent. for all others. “The miners were told that if they did not wish to work on the collieries they could leave. The company might take its own measures otherwise. The papers reported: “This ultimatum was strangely received by the miners, the majority of whom broke out into cheering and jubilation and fired crackers as the Consul drove off at 5 p.m.” Some miners held out for 50%, but the majority had returned to work by 20 November and the police guard was withdrawn. The number who refused to return to work were dismissed but the Colliery, who refused to tell the press how many this was. They rejected the report that they had failed to give the miners a chance to present their grievances, mentioning the previous harmonious record of relations between the company and its workforce. They added that it was fair to say that the workforce and the population had been thoroughly orderly and no property had been damaged. They increased their police force to 10 permanent police and two senior officers. It was at the time illegal to be a member of the General Labour Union, and two Chinese colliery workers, Foo Sin Ling and Yap Yin, were later charged in the K.L. police court as a result of the strike, one for being a member and the other for threatening Mr. Porteous although this second charge was withdrawn.

The Pavilion Cinema

On 26 July the Straits Times contained a detailed description of K.L. ‘s new cinema The Pavilion that would premiere with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in "Top Hat." It was built using 600,000 MalAcol bricks. An advertisement for the bricks with a picture of the cinema was on the same page. On 6 August the opening night was fully booked, with the police band playing in the orchestra pit beforehand. A distinguished audience included Bob Russell and Lola.

Rubber

Rubber companies showed a substantial rise in profits during the year. Bob Russell continued as director of Utan Simpan, New Serendah, Kamasan and Amalgamated Malay, until his resignation in November. Their company reports do not contain any description of labour troubles, although the smoke houses at New Serendah and Utan Simpan had been destroyed by fire. The intention of J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. was to sell all three of their rubber estates during the year, but there were initially no buyers. At Sungei Tua they built a new factory and smoke house and tapping recommenced in August. A new superintendant , Mr. A. H. Frugtniet from Ceylon was appointed, at a salary of $350 per month, and the labour force increased from 33 to 193. The tappers went on strike at the Bukit Bisa Estate although the Company felt they had been intimidated and were glad to back to work on 1 April. There were low crops due to the unsettled labour. The contract system was reverted to in August, with the rate raised to 80 cents a day in October, but production remained low and by the end of the year they decided to close the estate for 6 months. At the Russell estate concrete houses for 70 tappers were built by July, and the jungle on the reserve was felled for new planting. The estate was sold in August.

Malayan Collieries' Report

The Collieries Report showed that sales had increased by 34%, due to the higher tin quota that had been allowed. Production continued at Batu Arang, while the Borneo colliery was still closed. Coal production had been from the East mine, and from the gap between opencasts 5 and 7. A block in open cast 5 was being developed. Opencast 3 and 8 were the main ones producing coal. Opencast 9 was opened up. More capital had been spent on plant equipment. Electric shovel dragline machines and locomotives were being used to strip the shale. The construction of the railway line into the timber area had continued. More capital was needed and the company were going to issue more ten dollar shares. Temporary buildings and shops had been replaced with permanent ones, after fire had destroyed 36 shop houses and the Tamil’s housing. A new pressure boiler plant was proposed. During the year John Drysdale had again acted as H.H. Robbins alternate. There was a shortage of skilled underground labour. The strike, which had lasted 3 days, caused wages to be increased. The coal prospecting in Johore had stopped as they found that the deposit was not a commercial proposition. More prospecting was being done in the Batang Padang area. There was an improvement in the markets for their subsidiary products. The brickworks resumed production in January and there had been some large contracts including the building of the Rubber Research Institute. The plywood factory had produced 5 million square feet of plywood, and demand had increased. The sawmill had produced lumber which had been sent to London. The distillation plant worked all year. Apart from the strike the morale of the labour force had been good. The A.G.M. was to be held on 30 March.

Industrial Unrest

For many months there had been strikes all over Malaya. 44 estates were idle and roads had been barricaded. By 25 March the Malay Mail reported 30,000 labourers on strike, about 25,000 employed on rubber estates. There were other disturbances at Seremban. Arrests had been made on rubber estates and a meeting of UPAM had discussed the situation. The High Commissioner had arrived in K.L. and was meeting with the Federal Secretary. There had been roadways blocked but generally the position was quiet. The leader in the Singapore Free Press of 26 March pointed out that labour was not allowed to organise in Malaya and that they may have a genuine grievance. “It is, of course, as a result of the suppression of any organisation of labour that what, under normal circumstances, would be perfectly respectable labour leaders, are now designated agitators or communists.” The article suggested that the Government needed to find a balance to reach a peaceful and equitable settlement. A report of the Selangor Miners Association meeting in K.L. on 25th, recorded that the president Mr. Choo Kia Peng suggested that “employers must put their house in order.” He said labourers expected a share of the prosperity of their employers and that in Malaya there was no conciliation board. He traced most of the trouble back to the system of sub contracting labour, which resulted in there being little contact between employers and employees

Second Strike

At Batu Arang the miners held a mass meeting on 10pm on Tuesday 23 March and stopped work from 24th to 27th. The officials at the collieries believed that agitators from Kajang induced the strike, which was the centre of the rubber strikes. Those arrested at Kajang were in court on morning of the 25 March and were remanded till 30th, charged with” trespass with an intent to commit an offence”

Wednesday 24 March. Groups of pickets carrying sticks and iron bars were seen at the colliery. The colliery Superintendent F. Bellamy phoned the police at intervals during the morning. At about 8 am H.H. Robbins reported that most of the workforce were on strike. Even the plywood factory had closed. The water supply was cut off. Robbins arranged a meeting with the strikers at 1 pm with the Chinese Consul. The Assistant Protector of Chinese Mr. Broome left for the mine in the morning. The police turned him back feeling that with so few police and thousands of workers the negotiations should not begin until the authorities had time to send enough men to control what might happen. Strikers barricaded the road near the railway crossing with huge timbers. 50 police from K.L. and Rawang were sent to support the local force and mounted a guard on the power station. Two companies of the Malay Regiment, about 200 men, with 6 European officers and 4 warrant officers, were ordered to the Collieries from Port Dickson to guard the power house and machinery and assist 100 police already there. They were due to arrive at about 6 pm. At the one o'clock meeting Robbins was presented with a list of 23 demands. At 3pm the strikers marched round the colliery with their 23 demands written on a banner. In line with other strikers elsewhere they asked the officials of the company to use their influence to secure the release of 38 strikers held in custody in K.L. who had been arrested on the 13 March on the Kajang Road, and for an increase in wages. The Europeans managers spot 3 or 4 employees who were prominent in the November strike. At 5pm it was discovered that the strikers had captured a mine employee who they suspected of being a detective. The police tried to release him. The crowd demanded to talk to Mr. Robbins. Robbie and Bob Russell went with the police to find out if he was all right. They told the police not to take any action.

Thursday 25 March. Picketing continued. By the afternoon F. Bellamy told the police he was worried about safety. A minimum of 50 men were essential to man the pumps and inspect the mine for fire and gas but the strikers would not permit those men to work despite a request from the managers. European staff had gone underground to stop a fire spreading. The company offered an increase in wages of 10% subject to the safetymen returning to work. In K.L. the police briefed the newly arrived High Commissioner and the Protector of the Chinese. The strikers picketed parts of the workforce still working and offered them free food to keep them on strike. They were well organised and had control of the situation, the arrival of the Malay regiment had no effect. The road to K.L. was barricaded so that the reporter for the Free Press had to spend the night at the power station.

Friday 26 March. The fire was out but the lower levels had flooded. Two Europeans had been pulled out of car and insulted but had been ordered not to retaliate. H.H. Robbins told the police there was a plan to attack the power station. Barbed wire fence was erected around it. At 2.30 pm the strikers rejected the company’s terms. They wanted those arrested at Kajang released and a 50 % rise in pay. “ Mr. Robbins and Mr. Russell are bitterly disappointed at the complete breakdown of negotiations”. There were attacks on the Sikhs working the pumps, and the army protecting the fan. Bellamy thought that the miners would return to work if about 20 agitators were arrested. By the evening the police felt there was no hope of a settlement. Two companies of the Punjabi Regiment: 280 soldiers, with 8 machine guns were sent to Batu Arang from the barracks at Taiping. It was decided to make a raid on the striker’s headquarters. A further meeting with the High Commissioner was held at 8pm in the evening, He agreed to the police using whatever force was necessary to break the strike.

Saturday 27 March. With the backing of the High Commissioner and the Resident 200 Police made a surprise raid on a kongsi, which housed the strike committee, their prison and their weapons. The Malay Regiment was not used. As they arrived at 5 am in semi darkness they were met with a group of strikers holding crowbars, axes and poles who on the signal of a gong being struck and two whistles blown rushed the police. Under attack by the men, the police fired 9 shots from revolvers, killing one striker, and wounding 4 others. 116 arrests were made. The police seized documents and released three prisoners who had been held there for some days. The documents, according to the police, showed the close connection of the strikers with the Communist Party of Malaya. Although the police also added that the use of firearms had come as a shock to the strikers who believed that the British Labour Party was so powerful that the Malayan Government would not allow the police to use weapons. The prisoners gave statements to the police naming those in charge of the strike. After this the safetymen went back to work along with some of the miners. At 8.00am the company issued an ultimatum that the workforce could return to work or leave the property. At 9.15 am the company announced they expected normal working to resume. H.H. Robbins said he hoped production would commence the next day.

By 28 March it was reported that the strike was settled, and that wages at the mine had been increased by 10 % and work had resumed. By Monday 29 March the Malay Regiment were withdrawn. The police continued to make raids on the kongis which the strikers had used as headquarters, and made more arrests. Officials at the Collieries told the papers that they hoped to abolish the contracting system and establish a labour department where every employee was registered. They reduced the number of their contractors from 14 to 5. An editorial in the Straits Times on 30 March about the strikes had sympathy for the tappers but not for the strikers at the Collieries. It was their opinion that the tappers had genuine grievances and that planters had overlooked their wages. Tappers had no labour department to champion their cause. There should be a committee to watch the relation between profits and wages, the tappers had made sacrifices during the depression and a larger share of the current prosperity should be passed onto them.

The Collieries A.G.M. was held on 30 March with H.H. Robbins presiding. His speech included some solutions for the labour unrest. There was a shortage of underground labourers caused by the refusing of permits to Chinese recruiters of labour. There was profiteering by the steamships companies engaged in the transportation of immigrants, which the Chinese and Malayan Government’s should eliminate. The Indian Immigration system was much better. He felt that the attitude of the miners was of a growing unreasonable attitude in the two strikes within 4 months, the first in November and the second last week. The first had been settled without any action taken against what he called “professional agitators”. He felt that this had given them confidence, over an action that, in bringing a key industry in the country to a standstill, was aimed at forcing the Government to release the strikers arrested at Kajang. He said that the age-old custom of sub-contracting must be gradually eliminated. He suggested the setting up of some form of industrial arbitration and a wages board for the whole country.

The Company’s position had improved over the year. Having failed to find a workable coal deposit in Johore they were now looking in the Batang Padang district of Perak. They were still negotiating with “British Interests in cement manufacturing throughout the Empire” he noted the ominous international situation saying that paradoxically it was largely responsible for the company’s present prosperity. The board had decided to dispose of the Borneo Colliery. H.H. Robbins and Bob Russell were re-elected as directors. Mr. Lim Cheng Law was cheered when he said “ May I rise again to support that Mr. R. C. Russell be re-elected as a director of the company? I think Mr. Russell’s services are very well known to us all, and the resolution needs no words of recommendation from me. He is a worthy successor to a worthy and celebrated brother, the late Mr. J. A. Russell, whose memory is still cherished by the shareholders of the Malayan Collieries.” He was also applauded when he said, “I would like to see the inauguration of a department equivalent to a Ministry of Labour or the introduction of some efficient machinery sponsored and directed by the Malayan Government for the ascertainment, adjudication and settlement of industrial disputes between labour and capital. Had such machinery been in existence in Kuala Lumpur to-day, this strike would not have been thus unduly prolonged.”

The agency agreement between J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. and Malayan Collieries was due to expire 31 Dec 1937. It was to be renewed for 8/10 years. If the profits of M.C. were insufficient to pay a dividend of 10% there would be reduction in the agency fee.

Inquest and Enquiry

An inquest was held in Rawang from 6 May over the death of the dead striker. 22 witnesses gave evidence. It was heard by the magistrate of Ulu Selangor who found on 20 May that it was death through misadventure. The extensive witness statements by police, army and others to the inquest can be read here. The police were unable to discoverer the identity of the dead man whose photograph was shown to over 100 of the workforce.

When Archie died Andrew Beattie was one of his executors. He managed W. R. Loxley & Co. (London) Ltd. Although results for previous years had been bad, Don Russell had bought it, being assured by Mr. Beattie. Don described him as a "Plymouth Brethren with a bible on his desk who was as straight as a corkscrew." Despite Beattie’s promises, the business made losses and in 1937 Don's patience became exhausted and Mr. Beattie was asked to resign. H.H. Robbins, held Mr. Beattie in high esteem, but had no illusions as to his business qualifications and it is likely that he advised Don to visit London and look into the affairs of the Company. Mr. Beattie wrote to Mr. Robbins asking for help. Robbins, arranged that he should attend to Malayan Collieries’ matters in a letter dated 27/5/37, in connection with the engagement of staff with a retaining fee of £500 per year. In a letter dated 26/10/37 it was decided that as Mr. Beattie’s work had increased, and the whole of the agency fee was to be paid to him as from the 1st December, 1937.

Despite Bob Russell's high profile and his reception and re-election at the Collieries March A.G.M. at the end of 1937 he and H.H. Robbins had a disagreement and Bob was asked to resign from J. A. Russell and Co.Ltd. The Straits Times recorded Bob and Lola's presence with John Drysdale at a Durbar at the King's House on 12 November 1937. Bob had had 6 months leave from J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. from May to October. The meeting of 10 November reported his resignation being "accepted with regret”. At a later date Bob and Lola left for Canada. He was given an annual sum of £4,500 and the whole affair was kept quiet. Kathleen's notes refer to this here. Bob's letters to Kathleen record that Robbin's had told him: “Either you go or I go", and Bob's opinion was that Robbins wanted to " have me away and silenced". But as the minutes recorded the following year " Bob had taken " little interest in the business when he was paid to do so.”

The company had made repeated requests in the past year to the Government for permits for underground miners from China. They were not issued until June, by which time the selected men had been enlisted for military service in the war against Japan. Instead they had decided to mechanise their underground mining, and train their own labour force. He repeated his desire for co-operation between the Chinese and Malayan Governments over immigration on the same lines as that used in Southern India. He felt that the Chinese immigrant was exposed to exploitation, and the fact that India was part of the Empire and China was not had intensified the anomaly. Although it had been suggested that the Government should be responsible for the care of people who lost their employment during the slumps, he felt that employers of labour would be prepared to contribute to building up a settled reserve of labour. He welcomed the influx of female labour, which would create a locally born resident labour force who would stay in the country and keep their savings here, becoming self reliant, educated and being able to grow their own rice rather then rely on its being imported. At Batu Arang they had revised labour conditions. Workmen were being paid individually three times a month. Only one contractor remained and they now knew what each workman earned, what the deductions were, and the net amount received by each. A member of staff was responsible for all labour matters, and the collieries cashiers office was equipped to pay 1,000 individuals an hour on pay days. He was unable to predict the future due to the worsening international situation; although rearmament had increased trade there was still uncertainty. John Drysdale was invited to join the board, replacing Bob Russell to whom Robbins wished a long and happy retirement.

Malayan Collieries

The annual general meeting of the Collieries in March was presided over by H.H. Robbins. The issue of new shares had increased the capital. Capital expenditure on buildings and plant had been considerable. The village had been reconstructed with 56 shops, a market, and 15 of the permanent buildings of the old village were being converted into quarters for artisans. The new mechanisation was aimed at making the company less dependant on an unskilled workforce. The boiler plant had not been ordered in the hope of prices going down. Large sums were tied up in equipment waiting for installation, explosives or stocks for the subsidiary industries. There had been a high demand for coal during the year, and also a sharp increase in labour costs. The demand for coal was closely linked with the per centage of tin allowed under the restriction act, the year had ended with a fall in demand. They were restoring their stripped reserves of coal, and would reserve them as a standby for peak demand and emergencies. They had once again gained the contract to supply St. James Power Station in Singapore. Supplies of bricks and plywood had been good. The plywood chests represented 20% of all chests sold in Malaya. They were proud of supplying the bricks to build the Rubber Research Institute. The new railway to reach the timber area north of the Selangor River had now extended to the 10th mile and there were earthworks in advance of this. The line would be commissioned that year. (See map right.) The cement plans had made little progress and the Government ‘s attitude was ambivalent, and Robbins stressed the gain to the local people and industry if the plans went ahead.

Right: A Farewell Tribute to William Prentice reproduced in S.R.J.K. (C) CHAP KHUAN 90th Anniversary Book. Mr. Prentice had been in the news in July 1935 when he was rescued from the mine with H.H. Robbins, after being asphyxiated.

BATU ARANG 16th AUGUST, 1938. TO William Prentice, Esquire. UNDERGROUND AND OPENCAST UNDERMANAGER. MALAYAN COLLIERIES LTD., BATU ARANG, SELANGOR. DEAR SIR, WE the undersigned Contractors and staff of the Malayan Collieries’ Mines at Batu Arang in the State of Selangor, beg leave to approach you to-day on the eve of your departure to your homeland on furlough after a faithful and skilful service in the abovenamed Company, to express to you are sincere respects and to wish you a hearty farewell and a speedy return to our midst. DURING the tenure of your office when we have had the good fortune of working under your able guidance, we have found you to be sympathetic, just and kind to all of us irrespective of race, class and creed, and it is an immense pleasure we are now afforded the opportunity of acknowledging the straight forwardness we have received at your hands. WE sincerely wish you and Mrs. Prentice “Bon Voyage” home and pray that you may both live a long, happy and prosperous life, and all your future undertakings may be crowned with success. WE beg to remain, Sir, Your well-wishers, CONTRACTORS AND STAFF. CHU CHIU, LEE YUN, LEE LOONG, MAI TECK, SOO CHIN, CHU KHEE, CHIN WONG, CHEONG WAI, HIEW YEW, CHU YIN, LEE CHOY, YAP POW, CHU HIN, WONG LUM, WONG KOW, YONG SAIK, PANG KIT, TAI WONG, TOH FOOK CHYE, CHEONG AH KOW, YAP KIM FOH, WONG SIEW HUNG, NG PENG SUM.

Malayan Collieries The Collieries Report recorded that 1938 was a difficult year, they had earned more than half a million dollars, good results but less than the year before. There was a decrease in sales of coal and in their subsidiary businesses caused by the restriction in trade. Labour had been paid by the tri monthly system, which had been extended to all employees. H.H. Robbins chaired the 25th AGM held in March. In 1937 world trade had improved but the improvement had not lasted. There had been a surplus of labour, and while they had reduced the numbers, they had wanted to keep on a maximum labour force. So they had restricted the number of days worked by each person. They had continued to revise employment conditions until the last of the large contractors had gone. They now paid their workforce directly. Offers by the company to create individual, savings accounts had not been received with enthusiasm More women were employed, families were being encouraged to grow their own food and the company had stockpiled several months worth of rice in case the international situation interrupted supplies. With falling prosperity in tin mining that had been a corresponding decline in demand for coal. High wages and piecework introduced during the short-lived prosperity of 1937 could not be maintained. The Company wanted ways of adjusting these without depriving the labour force of the gains they had made. They had decided to make a sliding scale of coal sales with wages and piecework rates based on the prosperous year of 1937. All the workforce earnings were calculated and subject to increase or decrease based on whether the tonnage of coal sold in the preceding month was higher or lower than the peak month of 1937. They felt this eliminated the personal factor in adjustment to rates and conditions, especially over the time lag in the restoration of cuts, a factor that had caused much industrial unrest the world over. It incurred a heavy cost to the company in administering it. They were concentrating now on the amount of work done by each person per day and the introduction of mechanical aids to increase productivity to counteract the increased costs of labour. But with the falling off of demand it was becoming difficult to keep surplus labour employed. Some of the Colliery contracts had been very keenly priced and they were working within fine margins.

The plywood cases were selling well and a local product was useful in wartime. The wood preservative was still not selling well. The cement manufacturing plant was not finalised, although once again Robbins stressed the usefulness of having Malaya self sufficient in cement. He hoped that the best they could hope for was that rearmament would increase the demand for coal.

.jpg)

Kathleen's Marriage.

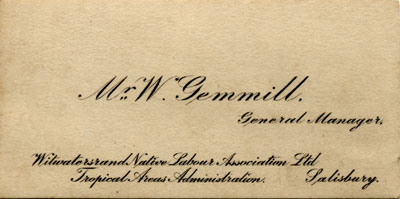

At the end of January Kathleen Russell married William Gemmill in Durban Natal, South Africa. A 53 old Scotsman he was recently divorced. He had trained as an actuary and was a tough and able administrator. He sat on the Transvaal Chamber of Mines and influenced the labour policies used in mines from the 1920s to 50s. He was General Manager of the Tropical Areas Administration of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association Ltd, in Salisbury. It is thought that he may have been advising Kathleen on J.A.R. & Co.'s businesses before their marriage.

Bob's concerns. At the trustees meeting in April Kathleen raised the issue of her letters from Bob. She said that Archie had talked of $1,000 per year for Bob to be retired on. It was agreed to increase the amount from January 1939. The allowance could not be borne by the trust and would have to be paid by the Company. It was agreed to send Bob the minutes, which he felt, were being withheld unreasonably.

In July Kathleen sent a confidential cable to Bob in Canada with copies of the J.A. Russell and Co. Ltd. minutes. H.H. Robbins was partially retiring. Bob gave Kathleen details of Robbin’s income. Bob was pleased about her marriage to William Gemmill; he assumed that William would look after Russell interests.

Bob wrote a letter to the board dated 12 July 1939 disagreeing with transferring three of Mr. Robbins shares to Delamore, Drysdale and Clarkson to provide them with voting power.

Bob told Kathleen he felt that there ought always to be a Russell on J.A. Russell and Co., Ltd and that “strangers” should not conduct its affairs.

War Time Collieries Strike

In December there was a third strike at the Collieries. Once again the strikers demanded a 50% raise in wages, with 18 demands in total. The wanted the abolition of the sliding scale of wages, and a reply to their demands in 24 hours. There was no picketing. The company pointed out that the sliding scale had been accepted for the past year. They said a 50% increase was unreasonable but they were willing to grant an allowance for increased cost of living due to the war. The men did not return to work and 150 police were sent to the mine. The men were told through loud speakers that the Government would not allow a stoppage of work of essential services in wartime. Delegates met the Protector of Chinese Dr. Purcell who told them that their action was unlawful as it might interfere with the conduct of the war. The Company met the representatives and offered an increase of $1.50 a month to cover the increased cost of living, and pointed out that the sliding scale system had led to an increase in 8% over the last few months. Only 300 Indians and Malays were working. The Indians were also striking for higher pay. The Chinese were reluctant to discuss the strike with the correspondent of the Straits Times. They believed they could find work on other mines if their demands were not met. Under the Emergency Regulations action could be taken against the strikers, although it had been stressed when they were passed that they should not be used to deal with industrial disputes.

After a series of meetings a settlement was reached very quickly. The Chinese Consul had meetings with H.H. Robbins, and later meetings with the men. The Company presented a budget for a workman for a month of $14. The Consul investigated this budget and made it $17. The Company said this was too high. The Consul then had a meeting with the delegates and H.H. Robbins, which lasted form 10.30am to 4pm without a break. The Company agreed not to dismiss any employees and to abolish its sliding scale system of wages. A definite percentage increase was what the workforce preferred. The company stressed that they were always ready to listen to grievances and had a labour department especially for that purpose. “Indeed, an outstanding feature of most recent strikes has been the tolerant attitude of both sides, and a desire to reach a mutually satisfactory settlement as soon as possible. This is well illustrated by the fact that at the end of the Malayan Collieries dispute, Mr. H. H. Robbins, the managing director of the company, shook hands with the workers’ leaders, a little incident which is far too rare in Malayan industrial negotiations….The chief lesson for employers is, so far as possible, to anticipate the workers’ needs, and for employees to refrain from unreasonable demands and to have patience in negotiating” reported the Singapore Free Press.

A serious fire which closed the East mine in 1939 was not reported in the Singapore papers.

Malayan Collieries

The report of the Collieries showed a sharp rise in profit with a dividend of 16 % for the year. H.H. Robbins presided over the A.G.M. Money had been spent on new buildings and more plant including a large electric dragline for the open casts. There were additions to railway rolling stock and to the plywood plant. Expenditure was down due to the temporary loss of underground production because of a fire in the East Mine, and the increased use of the opencasts. Income on coal was less due to low priced long-term contracts and a drop in rail freights. The year was dominated by the effects of the war, with reduced production of tin and rubber. The violent fluctuations in these two industries were in the hands of committees and the Collieries wanted to avoid their effects. They had hoped that their sliding scale of wages would help but had been told they were not in the best interests of labour. He discussed the transition of labour from Guilds to Contracts to its organisation into trade unions. He would like a clearer distinction to be made between reform and subversion and a procedure for rooting out those responsible for subversion or trouble would continue. He looked to the Government for a policy.

The fire in the East Mine had been severe and damaged plant, no lives had been lost. There had been a great demand for Plywood chests and they had bought plant to increase production by 50%. It was almost erected by the start of the war. They were able to supply the demand which had previously been met by the Baltic countries but was now lost through the war. They were selling a million chests each year. The saw milling plant had been re-housed and re-equipped. The demand for brick had fallen due to the shortage of cement for construction. The existence of a cement plant now would have been a great advantage to the country. Because of the war they were unlikely to commit any capital to it but limestone deposits were being drilled to test them.

The Colliery had bought a staff bungalow at Fraser’s Hill; since leave had been postponed due to the war he hoped it would be a pleasure to all concerned.

By September imports from Australia had ceased. Many estates had started to bale rubber in Hessian cloth but some had used the MalAply cases. By November the Collieries had achieved record production for the nine months up to September.

John Drysdale had to miss the monthly meetings of J.A.R. and Co. in June and October because of colliery business. In July it was found that since the previous August one of the clerks at J.A.R. & Co’s head office had manipulated the sales records of the Collieries Plywood department to defraud company of $1,200 to $1,500. The police were called, but the investigation was held up due to staff being mobilised with the local volunteers and in the end no action was taken. The accountancy system was overhauled.

Family Correspondence. Bob Russell was sent the minutes at Kathleen's request including all the back copies.

Correspondence from Bob, who was still living in Canada, to Kathleen in January showed was that he worried about H. H. Robbins continuing to sell income-bearing properties. An “orgy of selling” he says. His own income was dependant on the fortunes of the Company. He noted Robbins has not yet sold any K.L. undeveloped land. In March Bob wrote to Kathleen again commenting on the J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. minutes he had been sent, and H. H. Robbins salary of $2,000 a month. With other assets Robbins was receiving the same as a Governor’s salary of about $30,000 wrote Bob, who was still concerned with the selling off of assets. He talked about attempts to oppose H.H. Robbins by William, which seems to suggest that William is now a trustee.

Kathleen sent Bob a copy of a letter written by William to his co trustees. In Bob's reply he seems relieved to find that his worries over H.H. Robbins have been confirmed. He wants to give William his support & feels that H.H. Robbins should be removed as a trustee. Robbins was saying that the trust and the firm are two separate entities and Bob was arguing that the firm was the lifeblood of the trust, and that for Robbins as one trustee to have sole control of the firm was to have too much power. Bob was upset that the war had restricted travelling; he would like to meet Kathleen and William in England. In a second letter he was critical of Delamore who held the power of attorney and felt it should be someone else.

Malayan Collieries

The Collieries reported a production record for 1940, the highest in the history of the company. The demand was double that of 1939. Demand exceeded supply because of the loss of the East Mine in September 1939. H.H. Robbins presided over the A.G.M. in March. They had decided to set up an insurance for the underground plant against fire or flood after their experience with the East Mine in 1939. Working costs were up due to the increased costs of labour and materials. There was unprecedented demand for coal, which had to be supplied by the open casts. It meant stripping at greater depths, and they were unable to meet all demands. Contract consumers were being supplied at pre war rates; with these coming to an end revenue should improve. Costs were increased due to carrying large stocks against delayed arrivals from overseas. There was a war tax, their first experience of taxation. There was no increase in dividend since they felt they must conserve all resources to meet demand as a duty to the Government and the Empire. Plywood chests were meeting almost the full demand of the Malayan Rubber industry since no products from the Baltic were available. The emergency timber requirements of the Government had set up competition for forest labour, but timber supplies were now on the up. The brick works operated part time but they had now developed a new roofing tile, which was in commercial production. There were no serious labour troubles during the year. They were pleased to be able to deal with the local labour association which had grown in strength. The Company supplied rice to all its workforce at pre war prices and agreed to meet rises in cost of living based on a typical budget.

The Fourth Strike at the Collieries.

The whole labour force of 5,000 Chinese and Indians went on strike just before noon on 7 April. The Company had announced an increase of 7½% on basic wages on 1 April. On 7 April they offered 12 ½%. While the staff labour association was considering the offer a number of men stopped working. The committee agreed the offer in the afternoon by a vote of 31 to 35 and told the company that the men would resume work at 7am. But they refused and production of everything including the plywood factory was at a standstill. The Chinese Consul Mr. Tsze Zau Tsung was called in to help with negotiations between the labour association and the Company, which continued on 8 April. The Opencast men agreed to 15 % but the underground labourers asked for 20%. They blamed the cost of living particularly the rise in cigarettes. The Company then issued an ultimatum, which expired on 11 April. They were to return to work or be paid off and leave the property. The majority 3,200 were agreeable to 12 ½% but the Indian labourers would not return to work. After more negotiations on the 10 April some of the more technical workshop departments returned to work. Late on the night of the 10 April the Company issued a statement, which said that they would give the workforce another chance to return to work and those who did not would be paid off and expected to leave. Any people preventing men from going to work would be arrested. The workforce did not return to work. By 14 April the company withdraw their offer of the extra 5%. On 15 April 1,400 labourers were paid off and 500 told to leave Batu Arang. There had been a surprise raid by the police and large numbers had returned to work.

A letter to the Straits Times notes that workers at Home are “really under control” and pay tax while workers here are paid slightly more (49 shillings a week) and pay no tax and should be firmly dealt with.

In July Major G. St. John Orde Browne labour advisor to the Secretary of State for the Colonies arrived in K.L. and visited several large employers of labour including the Collieries. He met officials before going on to Perak.

Boh Plantations

In February the Accounts for the year showed a profit of $73,175.83. Boh was affected by the labour shortage. In March 50 Javanese recruits arrived, but labour was still short, it was planned to recruit 40 more.

Rates were increased and after a meeting with other estate owners in Highlands it was agreed to grant cost of living allowance of 10 cents, per day worked by both men and women from 1 May as against the previous bonus of $1 and 50 cents per month respectively. It was agreed to increase all retail prices by 5 cents per pound, which would cover the increased cost of production.

Sales: There wa a 8,960 pounds shipment to London in January to complete 1940 contract. There were local sales during January of 40,560 pounds, local demand was increasing, so it not necessary to make more shipments to London.

In March the crop was a record 58,000 pounds. Local sales were also a record of 43,780 pounds. The Ministry of Food had offered Company a contract for 1941 at same price as 1940. The contract was agreed covering 150,000 pounds up to February 1942, but in some months it couldn’t be sent due to the lack of steamer space. 6,000 pounds per month were sent to Australia (Melbourne) and by September local demand was in excess of supply.

They were still waiting for the Government’s agreement on exchange of lands in January. It had made a demand of quit rent on surrendered land of $3,400. This was disputed but in the end the Company agreed.

Boh Plantations Ltd. declared a maiden dividend of 5% on 11th August 1941.

In September Mr. Fairlie, the Superintendent, had joined the Straits Settlements Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve full time. The minutes comment: “Mr Fairlie’s lack of consideration of the Company’s interests was explained to Board”

The Company withdraw from Batu Arang on 5 January 1942. " Mr. Hinchcliffe recalled that sometime before the Company evacuated wages were computed every three days and during the last few days wages were computed every day. When it was finally decided to evacuate the property, wages for all labourers were computed. Pay chits were available to all labourers who presented themselves at the office. The majority of labourers collected their pay chits and money due to them while others , being frightened of Japanese bombing, had run away to the jungle. Mr. Hinchcliffe said he was present when an amount of unclaimed wages was paid over by the Company to two officials of the labour organization at the Batu Arang Police Station. The names of these officials were Mr. Yap Saik and Mr Woo Pin, and when the money was paid, the labourers were duly notified. Those who demanded their dues on the spot were immediately paid. European and clerical staffs were also paid off when the company ceased to operate."Mr. G. Hinchcliffe, a mining engineer at Batu Arang reported in The Straits Times, 19 February 1947, Page 5.

"With the advance of the Japanese late in 1941 the Company's stock of explosives and most of the mobile equipment, including tractors and bulldozers, were taken over by the Military. Principal items of plant were immobilized and the Power Station, sub-stations and main pumping units were destroyed to deny them to the enemy. Most of the European staff were members of one or other of the Defence services." Booklet on the Collieries dated 1950.

When the British Military arrived at Batu Arang they blew up the power station and looting began. The L.D.C. were ordered to take no action. Carrying his rifle Thiel Marstrand went back to the plywood factory to find it being looted and his own bungalow completely stripped. On his way back to the power station the village was buzzed by a Japanese plane dropping strips of paper. The following day the L.D.C. left with the few possessions they had managed to save. They travelled through destroyed estates with rubber on fire, part of the scorched policy of the army. In K.L. they were ordered to destroy as much wine and spirits as possible. The K.L. streets were full of rubble, broken glass and looted possessions. The L.D.C. drove south seeing wrecked cars and trucks all along the road, surrounded by columns of black smoke from the burning rubber estates.

The L.D.C. with Thiel Marstrand marched over the causeway to Singapore with the Argyles playing bagpipes and singing “Scotland the Brave.” In Singapore he met his wife and children again but learned that all their possessions had been lost. He was especially sorry to lose his stamp album. He met with H.H. Robbins who was trying to save what he could of the Company’s assets. Robbins provided the family with some cash. By the morning of 16 January his family left on a ship to Australia.