For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

Extract from a book of Drysdale Family History by Marjorie Heggen

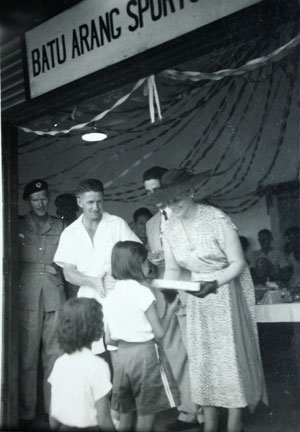

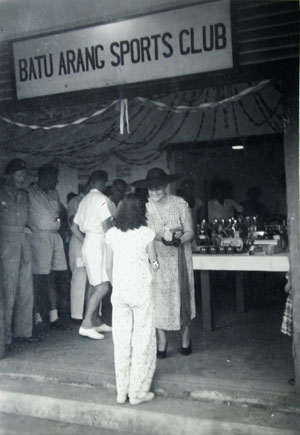

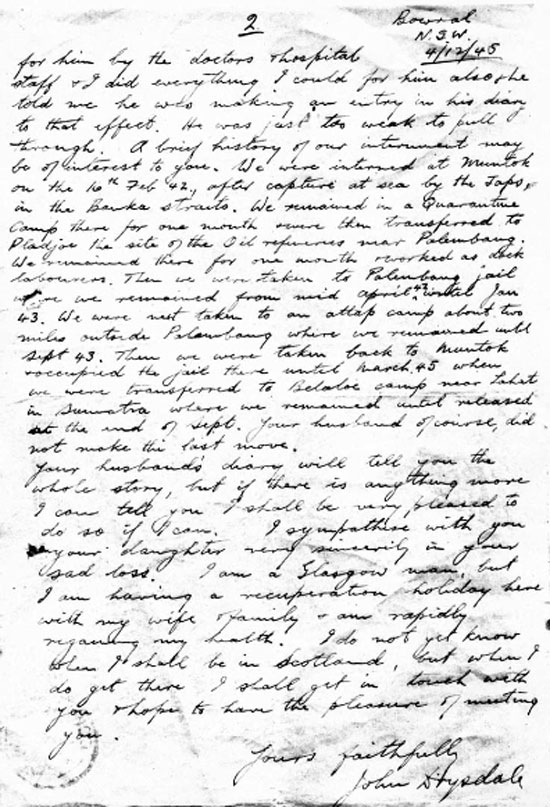

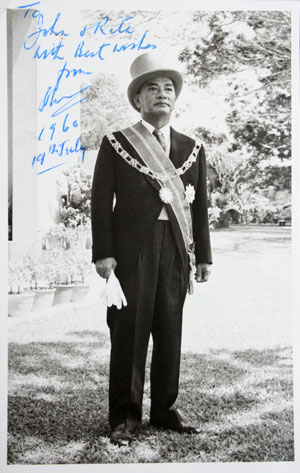

p. 216 By the time of the outbreak of the Second World War, John Drysdale was a company director with J. A. Russell and Co. in Kuala Lumpur, Malaya. He was in overall charge of the Coal Mines and Plywood Factory at Batu Arang and built the Wood Distillation plant there. p. 262 When war broke out in Malaya and after the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse on 10 December 1941, John Drysdale decided his family, consisting of his wife and two daughters, must leave. His senior colleague, a Mr. Robbins said they must join his family on their sheep station in Australia. Eventually they left and drove down the Malay Peninsula, meeting the Australian Army driving north. “They put us in the ditch once.” (1) The family stayed with friends while they tried to get a passage and left early in January 1942 on the SS Orion, after seeing the oil tanks bombed and burning. They made their way to New South Wales and eventually to Bowral, where they remained until after the war. In the meantime as the Japanese advanced south down the Malayan Peninsular, John Drysdale was involved in the “scorched earth policy” of the Administration helping to blow up bridges and dredges around Kuala Lumpur (2), before making his way to Singapore. There he helped to repair the engine of the SS Mata Hari at the request of a “Doc West” and as a result both men were offered passage on the ship (3) and escaped together. They were later also imprisoned together. Just ahead of the SS Mata Hari leaving Singapore was another ship, the Vyner-Brooke, which was also escaping with the American journalist William McDougall aboard. He was later to write about his experiences in captivity with John Drysdale and Doc West. The Mata Hari left the harbour of Singapore at night on 13-14 February 1942 with 483 men, women and children aboard, hiding among the islands during the day. The refugees wanted to reach the west coast of Sumatra or the island of Java. Unfortunately, Japanese warships arrived off the coast of Banka Island during 14 February. Next day the Japanese landed and captured Banka and the city of Palembang (on Sumatra). Thereby the escape route of the refugees from Singapore was cut off. Japanese destroyers discovered the Mata Hari, allowed the ship to surrender and escorted her into the harbour of Muntok on the island of Banka off the coast of Sumatra. The Mata Hari’s passengers were jammed into the old Muntok Prison and an adjoining building which had been used as a quarantine depot for coolie labour. In March 1942 the prisoners in Muntok were divided into groups. On 15 March 1942 a group of about 65 able-bodied civilian men were sent to the Shell Refinery at Pladjoe (east of Palembang on the River Musi) and put to work loading ships. One of these men was John Drysdale. One month later, on 15 April, they were transferred to Palembang Jail where another 420 men (Dutch and British) were already interned. They stayed there until 16 January 1943 when the 480 men were placed in the so-called Barracks Camp in Palembang. About 150 Dutch oil technicians, who previously had to repair the damaged refineries near Palembang, and nine boys from the women’s camp joined them there. On 18-19 September 1943 the 639 men and boys boarded a boat in the Musi river. It brought them to Muntok on the island of Banka. There they were (again) locked up in Muntok Prison. Subsequently, civilian internees from other places in southern Sumatra were also brought to Muntok. In February 1945 the prisoners were divided into three groups for transportation purposes. On 26 February, 5 March and 12 March groups of about 230 persons each left Muntok (it is not known in which group John Drysdale was transported). They were shipped to Palembang where they were loaded into waiting trains and brought to a little town called Lubuk Linggau. There stood a few “coolie lines” low wooden buildings with galvanised iron roofs. This became their new camp, named after the rubber estate “Belalau”. Here they stayed until after the Japanese capitulation. On 24 August the Japanese camp commander announced that the War had ended (it had ended on 15 August 1945). John Drysdale is mentioned several times in a book, By Eastern Windows: the story of a battle of souls and minds in the prison camps of Sumatra, by former internee William H. McDougall (an American) who had escaped on the Vyner-Brooke. In this book an incident is described that took place in Pladjoe (McDougall was not present there- he met John Drysdale in Palembang Jail)- p.263 For a month after their capture in February 1942, the Britishers had been forced to load ships in the Moesi River. The labour was strenuous and they were not allowed to rest. Drysdale finally rebelled. He sat down on the dock and announced he was going to rest for ten minutes. A guard pointed his rifle at Drysdale, ordered him to get up and resume working. Drysdale refused. “I’ll shoot”, said the guard in Malay. “Go ahead”, Drysdale replied, and remained seated. Other guards approached. Drysdale again was ordered to stand up and resume work or be shot. He again refused and repeated his defiant. “Shoot. I’ll work when I’m rested.” Instead of shooting they reported to the officer in charge who investigated and listened to Drysdale’s demands that he and the other men were entitled to rest periods. He agreed. Thenceforth they were allowed rest periods. However despite what Drysdale won for his companions, they were so frightened by his method-because the Japanese MIGHT have shot Drysdale and them, too-that they always mistrusted him. (McDougall, page 115) Maybe it was this incident that earned him the nickname “Direct Action Drysdale”. Later, as a member of the British camp committee in Palembang Jail, John Drysdale propagated an “active” policy towards the Japanese. The “active” school, headed by Direct Action Drysdale and Bard Curran-Sharp [the camp poet] favoured making formal, written demands on the Japanese that we be allowed to send our names to the International Red Cross and that we be given more medical facilities and better rations. The “passive” school opposed such action, saying it might provoke the Japanese and cause them to treat us still more harshly. (McDougall, page 86) John Drysdale also made an active and invaluable contribution to the daily life of whichever internment camp he happened to be in. He is recorded in McDougall’s book as being the “hospital chemist” and managed, with many experiments, to manufacture toothpaste which he sold at cost to the camp hospital. “As a profitable side line to his toothpaste trade, John Drysdale made toothbrushes from coconut and rope fibers.” He even made wristwatch bands scrounged from bits of metal from an abandoned aluminium mess tin and sold them to the prison guards. John Drysdale also made surgical knives and needles. He showed these, kept in a little cloth bag, to his younger daughter, Margaret, shortly after his release (he was very proud of them). Also, together with Doc West, they had manufactured fake sleeping powders and stomach pills as placebos with great psychological effect. Margaret Marsh also relates the story of her father on one occasion breaking out of camp to get food for a young Australian jockey named Jimmy Martin. After the war, in Sydney, Australia, John Drysdale and his wife were present at the Randwick Races to see Jimmy win his first race post war, a promise made in Prison Camp. Lending his watch to William McDougall when McDougall went “ubi raiding” outside the camp at night in return for a kilo of the root vegetable was another example of the exchange of services. Those prisoners who possessed a useful skill in a camp (the doctor being the most obvious) could then use it to buy a few pitiful extras such as smuggled food or medicines. Often it made all the difference between survival and death. William McDougall also gives an account of the appalling living conditions in the camps, the various deaths from beri-beri, malaria, blackwater fever (a complication of chronic malaria), dysentery, various fevers, ulcers, etc; also the starvation of the men. Red Cross food parcels did not penetrate into many of the Japanese prison camps in Sumatra. Life in Belalau was like camping out. The buildings were so vermin-ridden and hot. We spent most of out time out-doors, prowling for things to eat and wood to cook them. (McDougall, page 263) p.264 He also gives details of the number of dead buried in Belalau, “the cemetery in the rubber trees with its ninety-five graves”. 109 died in Palembang jail out of the 200 originally. In Muntok the death rate was nearly 60 per cent of the British Internees. In the Barracks Camp in July 1943, Drysdale tried to be elected as the British Leader in the Camp Committee. He ran only third in the balloting. He tried again on 7 February 1945 and this time John Drysdale did become leader of the British prisoners. He resigned after only five months as a camp leader. By this time the War was almost over. During all this time it was impossible to get news out of the prison camps so his family in Australia did not know for over three years if he had survived. He had written at intervals during 1942-43 then had stopped-no more paper. He brought the letters out with him on release.(1) In summary, it is possible to say that John Drysdale was in five different Japanese internment camps in the following order: 1. Muntok February 1942 2. Pladju 15 March 1942-15 April 1942 3. Palembang Jail 15 April 1942-16 January 1943 4. Barracks camp (in Palembang) 16 January 1943-18-19 September 1943 5. Muntok (again) 18-19 September 1943-February 1945 6. Belalau, South Sumatra February/March 1945 until after the Japanese surrender and from where he was released, sailing for Australia, New South Wales, embarking on 24 September 1945 per the Highland Chieftain. The only two very brief records in England of John Drysdale’s internment are as follows: There is a John Drysdale listed as being in a Sumatra Camp in Document W0208/1691 in UK Public Records Office Kew. The facts are minimal: Drysdale, John British b1897 Company Manager Sumatra. In a document in the Malayan Association Archives lodged in Cambridge University there is an entry: John Drysdale Malay Coll Sumatra. This overall list of internees and POW’s from Malaya was printed in Sydney, NSW in 1944 by the Malayan Research Bureau. That is all the documentary Evidence that has been found to date in the UK. (2) He eventually went back to Malaya to J. A. Russell and Co. and became chairman of the company. John Drysdale was awarded a CBE, 2 Malayan awards (JMN, PJK) because he was appointed to the Malayan Legislative Council and was also a JP. He retired to Scotland in 1962. He died in 1979 at the age of nearly eighty-two years. The inclusion of John Drysdale’s war experiences with the military biographies of the family is quite deliberate. He was a civilian internee of the Japanese and not in the military. Only recently has the experience of civilian Internees been recognised alongside that of military prisoners. The prisoners of the Japanese suffered most severely. The story of John Drysdale’s captivity deserves to be told.

John Drysdale b. 15 October 1897, Glasgow, Scotland. Son of Duncan Stewart Drysdale and Mary McLellan Jackson. John Drysdale was the third son in a family of five boys. Married 15 April 1926, Janet Margaret Wilton, Glasgow. Between 1917-18 he served in the Royal Flying Corps. He attended Glasgow University after the First World War graduating in mechanical engineering in 1925. By the time of the outbreak of the Second World War, he was a company director with J. A. Russell and Co. in Kuala Lumpur, Malaya. He was in overall charge of the Coal Mines and Plywood Factory at Batu Arang and built the Wood Distillation plant there. Civilian internee of the Japanese 1942-1945 Sumatra. Died 16 July 1979, Auchterarder, Scotland.

Footnotes page 262

(1) Written communication, Dr. Catherine Macdonald, John Drysdale’s elder daughter.

Braddon, Russell.

(2) The naked island. Ringwood, Vic. Penguin Books,

(3) Communication: Mrs Margaret Marsh, John Drysdale’s younger daughter who knew Doc West well in Kuala Lumpur after the War, as he was often entertained by John Drysdale and his wife.

Footnotes page 264

(1) Written communication, John Drysdale’s elder daughter, Dr. Catherine MacDonald.

(2) Details of records of John Drysdale’s interment held in England, contained in written communication by Ron Bridge to the writer, 6 February 2003.A Family Tribute to John Drysdale at his Funeral in 1979

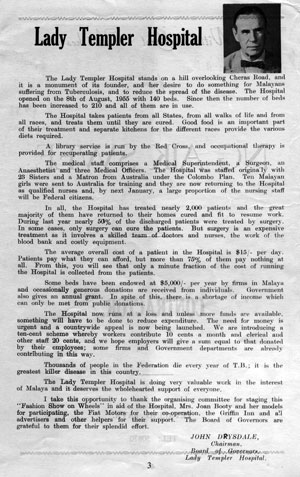

Family Tribute to J. D. at his funeral. For over 52 years, John and Rita, together have meant so much to so many. As a truly loving couple, as parents to Catherine and Migi, to their three grandsons, as very real and respected friends of the few of us here today, who represent the many who knew John and Rita in Gleneagles, since their retirement from Kuala Lumpur, where they had their home for over 30 years. It was in Malaya that John, with Rita at his side, served his Queen, the Selangor State, his Company, J. A. Russell, and the Lady Templar Hospital. For these services he was proud to receive the CBE, the JMN,(1) the PJK (2) and the lifetime honour of JP. Despite all these accomplishments, John was equally proud to be known as a good Engineer, getting his degree in Glasgow, starting work in Babcock and Willcox, and then the Royal Flying Corps, and rising to be Chairman of Malaya Collieries, and Malayan Cement, but also a Craftsman in his own workshop, not only capable of making surgical instruments out of scrap metal in a Japanese POW hospital, but most recently culminating in the restoration of violins down to the smallest detail, and not content with that learning to play the “blessed” thing, as he used to say. He was a truly contented and fulfilled person, Happy to be with his own family at Darquhillan, in the garden, or out improving his golf. Or pitting his skill on the loch with a rod, Or awaiting that fleeting shot at a pheasant, and out in all weather. For us all here today, There can only be Happy Memories of a Good Man, Loving, content and game to the last.

First page only from John Drysdale's letter to his wife in June 1942 and page 18 only from his diary from 1943

Palembang Sumatra 19th June 1942 Good morning darling, A happy birthday and many happy returns of the day and I do hope you are not worrying unduly about me. I am very fit and well and am making the best of an unfortunate position along with Ritchie and Anderson of Ritchie and Bissett Singapore and many others that you know. Robbie was with us until the 20th April, but as you probably know by now, he died on that day of heart failure as the result of weakness following an attack of dysentery. We did everything we could for him, but he hadn’t enough strength to come through. I wrote Joyce at the time, but so far I have not had the opportunity of posting the letter and still have it with me. I shall cable as soon as I am in a position to do so. I think of you, Catherine and Margaret, Joyce, Anne, Mary, Hilda and Judy and Muriel every day and pray that you are having a happy contented time together at Oran Park. Robbie and I used to talk about you all and wonder what you were doing at particular times of the day, now I have to make those pictures myself, but I continue to make them and shall continue to do so until I join you there and that will be as soon as I can do so. As you will see from the above address, I am in Sumatra and our quarters are at the gaol in Palembang. That perhaps sounds worse than it really is; actually we are all reasonably fit and well and as happy and contented as circumstances will allow. On the whole we are faring not too badly and could be much worse off, but the aim and outlook of all of us is to be free again to join our loved ones and get back to work. In my letter to Joyce I outlined what had transpired from the time you had our last letters from Singapore which was about the 8th or 9th of February and the 20th April the day on which poor Robbie died. I don’t know whether you will see Joyce’s letter before you get this one, but in any case I do not think I can do better that give you also a resume of what …..

18

July 1943 Started making and rebristling toothbrushes for hospital revenue…in hospital with foot sores. Selling watches to Jap. Officials on 10% profit… food position. Change of Camp Management, Resident Oranje, Van Asbe…..management committee. British committee disbanded. Ambonese said to be rounded up by Japs and Dr. Zeisal of Charitas arrested. News of landings in Sicily and…. Italy and fall of Mussolini. Had severe bout of diarrhoea.

Aug. 43 News re landings in Albania etc and naval battles in Pacific. Started making ointment in hospital. Enjoyed good cabaret show. Celebrated first anniversary of engineering association with J.D. as chairman, Resident Hammett, Van Arbel and Haines as speakers. Harrison? elected new chairman. Eighteen months since leaving Singapore. News of Churchill and Rosevelt in Canada. Typical day in camp, roll call 6AM, coffee 6.30, Breakfast 9 AM, Gaplek and Soya bean porridge. Coffee 10 AM, library 9-10. Surgery 8.30-10. Tiffin 12.30, (sago/vegs/eggs), fish or meat or nut sauce, soya beans and chillie, tea 3.30 (½ a mug) library and surgery, roll call 5.30, supper 6 pm, obi kayu, vegs, soya bean and sweet sauce. 9 pm lights out! Played bridge most evenings and read after tiffin. Working at hospital mornings and afternoons. Gave talk on return to Malaya. Harley Clarke talked on “Sources of the Nile and Dr West on The Medical Practitioner and his training and Wright on Palm. oil machinery. Some Palembang officials taken out of camp by Japs. Stalin said to be complaining of no second front. Queen Wilhemina’s birthday 31st celebrated with nasi goring and fried balls , and coffee and cakes in evening.

43 Fourth anniversary of World War, 3rd Sept. Further news re capitulation of Italy and of allied attack on Marquese Islands. Anderson went into Charitas hospital with tummy trouble. Charitas hospital disbanded and Dr. Tickelenberg came to camp hospital required by Japs. Resident and other Palembang officials return to camp looking like beachcombers! Talks by Douglas—Malayas War Effort, Oosten Growth of Royal Dutch Oil Co. Bergmeyer—Photographic Technique. All camp meetings prohibited. Camp moved to Muntok gaol, travelled by lorry and Penang Ferry boat (Bagan Seriah) Baggage examined on arrival. Spent uncomfortable night on concrete floor 2’-4” allowed per man. Later I fixed up my camp bed on verandah & made myself, Richie and Anderson comfortable with shelves on wall etc. Celebrated Margaret’s birthday on 20th. Change for the better in the Jap attitude towards us and the air at Muntok an improvement on Palembang, horrid mud, & better water supply and bathing facilities. Census of money taken at Jap. request. Food poor but improvement promised, really only one meal per day and no veg or fruit etc. 130 men from Djambi and Bengkulen join us. Five Britishers one from K.L.

Oct 43. Celebrated 34th anniversary of Ritchie’s arrival in Singapore. Anderson out of hospital and joins R and J. in block 2. Rumours that Burma in Allied hands and that Germany capitulated. Occasional planes patrol overhead. Water short and supply carefully regulated and well put into use. No clothes washing allowed and children taken outside to bathe. ARP exercises practised and air activity increase. Some rain & water supply improved. Rain through roof onto bed. Several officials rejoin us after trying time, also Cruikshank (A?). Hot water boiler and library built in camp. Several deaths occurred including Sir John Campbell. Brodie and Starkey build model yacht. My weight is 9 st 12 lbs i.e 1 st 7 lbs less than normal. Japs prohibit use of private cooking fires that were being used in various parts of camp for re cooking food and cooking extras purchased. 30 kgs of pork given one day for tiffin i.e. 1 ½ ozs per man. Rice ration cut from 200 gms to 140 gms per man but made up with soya beans. Sugar issued twice during month. Rumours re capitulation of Germany and of sea battle off Soeraboya and that Danzig and Budapest in Russian hands, also fighting in Poland.

Nov. 43. Am still well and fairly fit and manage to pass the days in a more or less interesting way…whatever interesting books are available and generally try to improve my mind get much pleasure and benefit from the Classics. I am especially interested at the moment in philosophy and religion. Cut off all my hair to reinvigorate the growth. Nice & cool but doesn’t improve my appearance. I have now been going about with bare feet since leaving last camp and am now quite used to it and prefer it to ?kerompak or clip-clops. Studying Principles of Industrial Organisation. Japs again prohibit contact with outsiders or guards also purchases from outsiders. Food supply the same but managed to buy some onions which we chopped up and ate raw with tiffin, we also germinated green peas and mixed them with breakfast and porridge. Shortage of soya bean experienced. Other two deaths and two attempts at suicide. Other eight men join us from Bengkulen. Celebrated St Andrew’s day with coffee and obi cakes. Present food-Breakfast gaplek porridge to which we add peas or onions & a spoon full of sugar. Tiffin-170 gms rice, vegs, fish or meat sauce (1- ½ ozs) Coconut or bean balls. Obi or soya bean (20 gms) + chillie. Supper-obi, bean sauce and 2-3 small dried fish. Two Jap officers visit camp and inspect accommodation. Ritchie has heart attack and suffered some pain. Cooked up some obis, onions with coconut oil in ash pit of hot water boiler and result very good. News of allied naval activity in Pacific.

Dec. 43. Ritchie into hospital with heart trouble. Anderson and I quite fit. Second anniversary of Jap war 8th Dec, Jap flags up and some outside celebrations. Rumours re battle at Marshall Islands and allied progress in Burma. Enjoying snack cooked each day in ash pit of boiler Enjoyed Christmas celebrations with extra tit bits eg….. No more paper – no post.

John Drysdale's letter to Thiel Marstrand, after reading his memoirs.

25/9/78 ……… Dear Thiel, Further to my letter of 13th Sept when I ack’d receipt of your Malayan record, Rita and I have read your memoirs with much interest and we both feel that you (are to) be congratulated on conducting yourself in a highly disciplined and highly principled manner throughout your many and varied experiences. “No medals” by Thiel Marstrand should we think be entitled “No medals, the saga of Thiel Marstrand during the Malayan Campaign.” It makes very interesting reading and I recollect all the individuals, both European and Asian that you mention including your mill workers and office staff and on several occasions I was reliving incidents to which you refer. As far as medals are concerned, I think you, as an active member of the L. D. C., were entitled to the Malayan Defence Medal and I believe that if you had returned to Malaya after the war you would have got one and I think Jack Draper would agree; so that maybe some consolation to your little grandson John. I got one for my A. R. P. service. My work was regarded as of National importance and I wasn’t allowed to join the L. D. C. (I was over age anyway) but I was allowed to do ARP work in my own time and when other duties allowed. The fact that I was not a member of the L. D. C. had unfortunate repercussions as my wife was not entitled to any allowance from the Malayan Govt. while she was in Australia. Fortunately, she had good friends. I was interested to note that your friends at Batu Arang were among the nicer ones. An incident which made me sad was your experience with Mr. S. when you returned to Batu Arang after your leave in Norway. I suspected that Mr. S. was trying to undermine your position during your absence and I used what influence I had in trying to counteract it. It was an unfortunate and most undeserved experience for you while it lasted, but you came out of it well in the end. I never liked Mr. S. Some happy interludes among your experiences were your contacts with your Norwegian sea-faring friends and the further contacts you had with some of them later. The circumstances of your return to Batu Arang through the medium of your mill workers was I think unique that and your experience with the Japanese officials make interesting reading and the loyalty of your workers says much for your humane treatment of them. You met some good Japs and some bad ones, so did I, but I’m glad you met more good ones than I did. When reading of the lesson taught you by Mrs Michaelson at the Danish Consulate, I was reminded of a similar incident concerning myself in our prison camp in Sumatra. I had been working hard for the welfare of my fellow prisoners and an old friend took me aside and spoke to me as Mrs M. did to you and like you I accepted good advice. Your position during the war period being Norwegian with Danish associates was rather unique and your experiences at Batu Arang, Singapore and Cameron Highlands were at times amazing and well worth recording and I think your decision to put it all down as you have done provides a family record of which the various members should be proud and Rita and I feel privileged in having a copy of it. My elder daughter Catherine was always interested in the Plywood Factory at B. A. She often speaks of it and says she liked the smell of the hot veneer, so I intend letting her have perusal of your memoirs and I am sure the others will also wish to read them. I shall read them again, more than once and will always feel in close association with you. Again, many thanks and with kindest regards and best wishes to you all from us both. Yours sincerely John Drysdale.

J. D. worked in Babcocks Glasgow office. BABCOCKS Boilers in Malaya used Batu Arang coal. A Babcock man going round Malaya visited Batu Arang – J. A. was impressed with his visit and offered him a job, but he couldn’t take it. J. A. said he wanted a man with similar experience. J. D. had visited most power stations in the U. K. J. A. interviewed J. D. driving around London in a sound proofed Rolls Royce. They had a chat, had lunch together, and signed and confirmed the job.

Notes from conversation with Rita Drysdale.

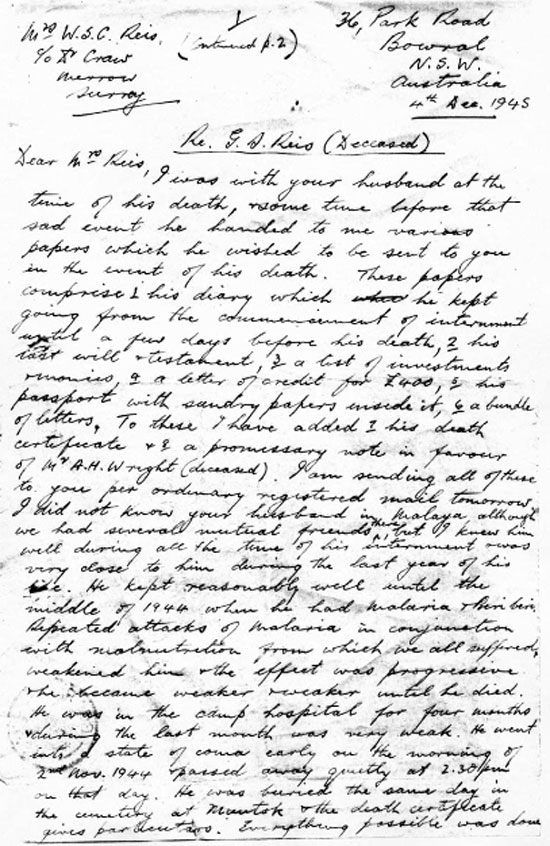

The diaries of fellow prisoner at Muntok, Gordon Reis are on line. They mention H.H. Robbin's death and the file contains two documents on pages 62- 64 signed by John Drysdale: a sworn declaration of Reis's death and a letter to Reis's widow, (also see below).

GOVERNMENT Of THE MALAYAN UNION STATE OF SELANGOR STATUTORY DECLARATION. I, John Drysdale, of Kuala Lumpur, Director of Companies do solemnly and sincerely declare as follows:- 1. From the 16th day of-February 1942 until the 2nd day of November 1944 and afterwards I was a Civilian internee in the hands of the Japanese in the Muntok & Palembang Camps, Sumatra, in the Dutch East Indies. 1. One of my fellow Civilian internees in these Camps was Gordon Stanley Reis whom I knew as a planter of Batu Kawan Estate, Province Wellesley, Malaya. — S. The said Gordon Stanley Reis died in Camp on the 2nd day of November 1944 and the reason for his death was beri-beri due to malnutrition by reason of the shortage and nature of food and inadequacy of medical treatment and the conditions under which be was obliged to live while as a civilian internee. AND I make this solemn declaration conscientiously believing the same to be true and by virtue of the Statutory Declarations Enactment. SUBSCRIBED and Solemnly DECLARED by the said JOHN DRYSDALE Kuala Lumpur in the State of Selangor this day of 1946 Before me:- Magistrate, Kuala Lumpur. sgd. J. .Drysdale.

The right hand side of the diary is torn for the first 3 lines and the last 3 to 4. Missing words are represented by .....

Notes: Gaplek is the sliced dried root of cassava and obi kayu is mashed tapioca cake.

kerompak are clogs or sandals.

Christmas in 1951. Alan Llewelyn, his mother and wife with the Drysdales at No. 5 Hampshire Drive. Photographed by Malcolm Llewelyn using his box brownie camera.

In 1952 JD joined the Federal Advisory Board.

John Drysdale returned to Malaya in 1946. He found the Colliery full of “Banana Colonels” trying to run affairs without any previous knowledge. By 1947 he had negotiated with Portland Cement to set up the cement factory. In 1948 the colliery was attacked by bandits. During the emergency he oversaw the development of new schools at Batu Arang in 1949. The cement company was formed in November 1950, the same year that his fellow director Clarkson was killed by bandits. Construction at the cement factory site began in 1951. The Drysdales now lived at Number 10, Hampshire Drive in K. L. (now Persiaran Hampshire). During 1953 JD was targeted by bandits on his route to Batu Arang. A compradore for J. A. Russell, Chong Kim Voon saved his life by coming round to Hampshire Drive early in the morning to warn him of the ambush.

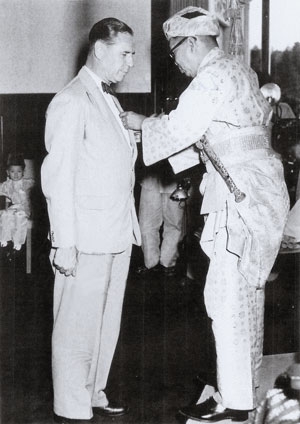

In 1959 the cement works expanded and its extension was opened by the Sultan of Selangor. Left: Introducing the Sultan to Mr. H. J. Hamilton, the works manager. For more pictures of this event click here.The cement works went on to provide cement for some of the largest building projects in Malaysia.

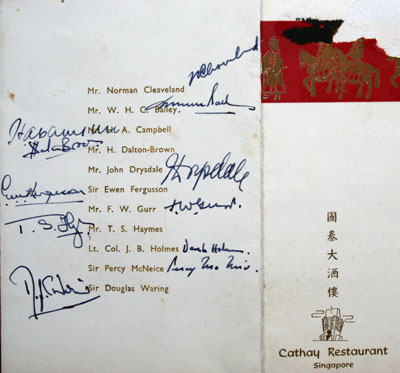

Left: A meal at the Cathay Restaurant, Singapore. John Drysdale on the left. Possibly Sir Ewen Fergusson in the centre in front of the pillar , next , Sir Douglas Waring and Sir Percy McNeice. Two from the right Fred Gurr.

W. H. C. Bailey was chairman of Harper Gilfillan, the distributor of Boh tea and had been a director of the Collieries. He retired in December 1962. John Drysdale retired the same year and Alan Llewelyn become chairman.