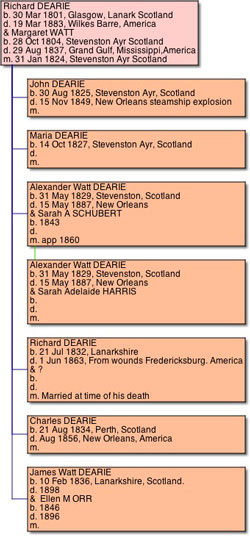

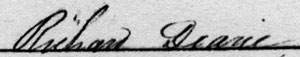

For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

Richard Dearie 1801- 1883

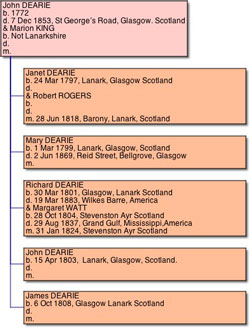

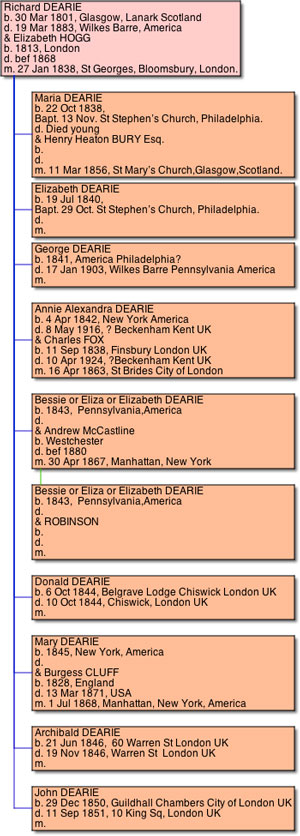

Richard was born in 1801, the eldest son of John Dearie a weaver, in Glasgow, Scotland.

He described himself as: Collecting Clerk, Gentleman, Custom House Agent, Commission Agent, Collector to a Brewer, Innkeeper, Wine dealer, Licensed victualler, Wine merchant, and Distiller.

Glasgow Weavers

Glasgow had a population of about 60.000 in 1800 and weaving was the main occupation.

Richard was born in the parish of Barony, which stretched to the North and East of the city. Calton, part of Barony, was a district then just outside the Glasgow city boundary where most of the population were weavers, so it is possible that he lived there. Most of them would have been handloom weavers which was a skilled and profitable trade that afforded a better than average life style.

The weavers were well regarded for their high standard of education and their social awareness. They tended towards more radical political views and this made them less popular with the authorities.

Towards the end of the 18th century there was a serious decline in their fortunes. Their numbers grew with many of the new workers offering lower prices. In addition, the import of cheaper textiles from India caused a further fall in prices that seriously affected the industry.

The Weavers Strike

The trade involved manufacturers providing raw materials to the weavers. Once they had negotiated a price they made the cloth and were paid when it was returned to the manufacturers. In an effort to keep their costs down the manufacturers reduced the prices they were prepared to pay. Following two significant reductions in price within a period of seven months the weavers held a mass meeting on Glasgow Green that took place on 30 June 1787. They felt they could not live on the remuneration offered by the manufacturers and agreed that no more work would be accepted at the new low prices. Four weeks after the strike began the manufacturers retaliated by giving out no work at all.

The dispute reached a climax on 3 September 1787 when a crowd of weavers seized materials from those still working. The town authorities attempted to intervene but were forced to retreat under a hail of bricks and stones. The military was called out and the soldiers opened fire. Three demonstrators were killed and others were wounded. Many arrests were made: some were imprisoned and some forced to leave the country. The dead were regarded as martyrs. Terrible poverty followed the strike.

Richard was born in 1801. Between 1800 and 1808 the income of the weavers halved. In 1803 Napoleon was preparing to invade England. In 1811 there were Luddite riots, as many traditional crafts were replaced by mechanisation and workers feared for the loss of their livelihoods. In 1812 America declared war on England. Another strike from 1811 to 1812 failed to achieve fair wages for the weavers. In 1815 there were riots against the Corn Laws, and by 1816, after Napoleon was defeated there was mass emigration to America and Canada. The Prince Regent’s coach was attacked and habeas corpus suspended.

During this period of painful social change Richard was educated at the school of Sheridan Knowles and became, according to family history, a poet and his prize pupil. Knowles ran his school between 1813 and 1825. He was well known at the time and this may indicate that Richard’s father John had enough money to send him to Knowles’ school.

Work and Marriage

It is not known at what age Richard began work; some young men were apprenticed at the age of twelve. He followed in his father’s profession and began work in a mill. Many mill owners took the education of their workers seriously and provided schools for them.

Attempts had been made after the war with France to relieve the hardship caused by unemployment, but charity did little to relieve the problems. The radical movement grew amongst the weavers and government spies were ordered to infiltrate them. The Scots resented the fact that they had fought against Napoleon only to find their real needs for social justice ignored on their return.

The Scottish Insurrection

In 1820 when Richard was 19, the Scottish Insurrection took place. Throughout Scotland on 1 April 60.000 stopped work. The authorities fearful of what might happen lined the streets of Glasgow with soldiers. Troops advanced on a group of seventy radicals to disperse them and some were wounded. Forty-seven were rounded up and put in prison. Twenty-four were tried and sentenced to death. One of the three executed was a 60-year-old weaver, James Wilson. He was hanged and quartered on Glasgow Green, watched by twenty thousand people. Two other weavers were executed in Stirling watched by a crowd of two thousand. Nineteen others were transported to Australia.

It is not known what the Dearies felt about these events or whether they were sympathetic to their fellow weaver’s radical views. We only know that Richard’s family was a strict Presbyterian one. Their lives must have been affected by the economic circumstances.

Four years later in 1824, at the age of 23, Richard married Margaret Watt from Stevenston. This parish covers Stevenston, (still a very small place today), but also includes Saltcoats a busier dock area on the coast some thirty miles to the west of Glasgow.

From the following year until 1836 Richard and Margaret had six children. At some point in 1834/1835 he moved to London. Whether his wife came with him is not known. The workers at the mill gave him a snuffbox, and he took with him a certificate of good conduct. Were the reasons economic ones? Both his younger brothers had emigrated to the US already one in 1827 and one in 1830.

London

In London Richard suggested to William Burnand, a coach maker in the Marylebone Road, that he set up a wine and spirit business, selecting the goods from the wholesalers, and serving customers. He started work on 1 January 1835 working for the sum of 30 shillings a week, plus commission of two and a half percent on goods sold after six months.

He worked there for 2 years. He spent his day until 2 pm at the docks and other places on business and then from 2pm to 8pm he served customers. Burnand dismissed him on 31st December 1836.

Richard set up a rival business a few doors along from his previous employer on the 2 January 1837, with a partner called Mould. William Burnand then took out a warrant for his arrest for embezzlement and on 4 February Richard was arrested. His new partnership was dissolved in February 1837, before the case came to court. The case was heard on 3 April at the Old Bailey Central Criminal Court. He was found not guilty. Read the whole case here:

In the summer of 1836 his wife deserted him. He went to Scotland to search for her, but she left for New Orleans at the end of the year, taking their children with her. The passenger list for the ship Agnes and Anne lists only five male children. Maria may have already died.

Richard returned to London without his family, with no work, and faced the possible loss of his good name as a result of the court case. Was he employable? At some point in the autumn of 1836 he had a relationship with a Mary Anne who had a son named Frederick in June 1837, born in Kings Road, Pentonville which is now called St Pancras Way. Was Mary Anne the reason his wife left him, or did he turn to Mary Anne after the event?

His wife Margaret died in New Orleans in 1837. It is not known if he managed to meet up with her again before her death. He didn't stay with Mary Anne because six months after her child was born, he married Elizabeth Hogg.

Glasgow

The following year in 1856 Richard’s son Charles by Margaret Watt also died. By this time Richard was running three different drinking establishments in Glasgow.

His daughter Maria aged 29 married Henry Bury of New York at St Mary’s Church in Glasgow. They seem to be doing well; someone paid for the marriage to be announced in the paper. Henry worked with Richard running the pubs. But the alcohol they sold had been made in an illicit still at 81 Glassford Street underneath the Glasgow Trades Hall, and was discovered by Inland Revenue officers in March 1856.

Richard was out of town but Henry; his son in law was fined £30 on the spot and had the money to pay up straight away. Mr. Ebenezer Taket, Richard’s employee was taken before the Justice of the Peace and fined a few days later, but held in custody since he could not pay.

The cheek of operating an illicit still underneath the Glasgow Trades Hall may have contributed to the massive £3.300 fine Richard later received.

London

The news in the Glasgow and Edinburgh papers was copied in the London dailies. It was the biggest haul of illicit alcohol ever found in Scotland. Richard tried changing his name to Robert and moved to 2 Murray Street New North Road in London, but was caught and ended up by 1857 in Whitecross Debtor's Prison in London, which stood where the Barbican is today. Did the family join him there? Annie was taken away to be brought up by her Uncle.

By April he was in the Insolvent Debtors Courthouse in Portugal Street, Lincolns Inn Fields for the relief of his debts. There were also proceedings against him about the estate of his father.

In 2010, the relative value of £3,300 0s 0d from 1856 ranges from £241,000.00 to £6,260,000.00.

New York and Wilkes-Barre

The American Civil War began in 1861 and continued till 1865.

In 1863 Richard was living in New York and lost another son, Richard who died at the battle of Fredericksburg. His son George survived the war although he was captured at Gettysburg. Richard stayed in New York and can be found in the records distilling whisky and paying taxes there in 1865 and in 1866 with his son George, at Broadway 54 and 55. In 1867 his daughter Bessie married Andrew McCastline in New York and his daughter Mary married Burgess Cluff in 1868.

In New York in same year, 1868 Richard himself married for the third time, a widow called Elisabeth Guthrie from Donegal, Ireland. It can be assumed that Eliza had died; but it is not known where or when.

George was living in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania by 1871, and by 1873 Richard has moved there too. He is recorded as selling wines and liquors on the corner of Market or at Public Square from 1873/74 to 1882/84, with George at the same address.

In 1 May 1876 Richard applied for a licence for a restaurant in Wilkes- Barre and on 19 April 1880 he applied for a liquor licence. By 1880, his third wife also dead, Richard was living with his daughters Mary and Bessie, both also widowed in New York.

A Richard Dearie was on board a steamship bound for Glasgow in July 1880 with a Mrs. Mary Cluff, but that might not be him.

The one photograph that we have, shows him in his old age. He appears to be blind and it was something his son Jack was very afraid would happen to him. Drinking, especially “moonshine” can be the cause of it.

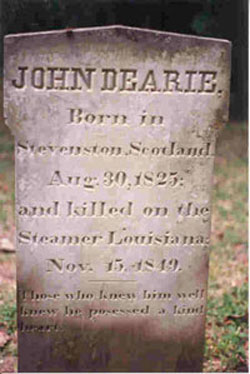

On an old family tree Gertrude Fox had written of Richard, “six sons killed at Gettysburg.” It is interesting how these bits of information contain partial truths. George was captured at Gettysburg but did not die there. Richard did lose 6 sons: 1. Donald at Chiswick, aged 4 months, 2. Archibald at Warren Street aged 3 months, 3. His eldest John in a steamship explosion in New Orleans, 4.His baby son John of whooping cough, aged 9 months. 5. Charles in New Orleans, and 6. Richard at the battle of Fredericksburg.

Relieved of his debts an 1860 London street directory places him running a lodging house at 2 Chapel Street West Mayfair; but by the time it was printed, he was back in New York arriving on a boat on 15 August 1859, with his two daughters, Bessie and Mary. Whatever they thought about his behaviour with their half sister it seems that they have stuck with him, and been prepared to leave their sister Annie behind.

Step daughter Jessie stayed in London called herself Mrs. Russell and brought up her son John on her own by running a lodging house.

Daughter Annie brought up by her Uncle Robert Rough married Charles Fox in 1863.

Right: Chapel Street. The house is now demolished, but these are left on the other side of the street.

Richard died of pneumonia on March 19, 1883 in Wilkes-Barre. The Wilkes-Barre Record of Tuesday 20 March 1883, p.4 says: "Death of Richard Dearie. Yesterday afternoon Richard Dearie, Esq., died at his residence on South Main Street, aged 83 years. Mr. Dearie was a native of Scotland. He first came to this country in 1836, but after a short sojourn returned to Europe, where he remained several years. On his return here he became engaged in business in New York, and finally in 1870 moved to this city, where he resided until his death. He was well known here, and was respected by all.

The Wilkes-Barre Record of Thursday March 22, 1883. p. 4 "Yesterday afternoon the remains of Richard Dearie, Esq., were consigned to their last resting place. A large number of friends were present at the funeral ceremonies, and a lengthy cortege escorting the remains to the place of internment."

The records of the City cemetery show that the information about him was registered by his son George. He was buried in a plot owned by George. His birth is recorded as March 31, 1800, although Glasgow records show it a year later in 1801, making him 81 years old. He is buried in plot 139. (Pictured left.) There appears to be no grave stone.

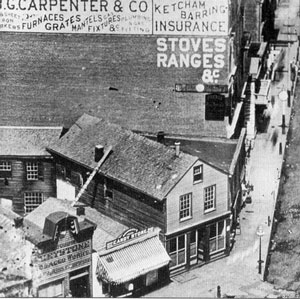

Above:Wilkes-Barre in 1880

Below: 57 Public Square in Wilkes-Barre, the corner of the west side of Public Square and West Market Street ; listed as Dearie's Hotel in 1889, and known for many years afterwards as "Dearie's Corner"

Left: No. 9 Soho Street. Known as Charles Street until 1884. The Fish and Bell was renamed the Coronet by 1895 and was still a pub in 1975 which occupied both the restaurant on the left and the Krishna Temple currently on the site. The Post Office Directory for London for 1849 lists No. 9 Charles Street "Fish and Bell" Richard Dearie. Next door at No. 10 was Egbert Lamley, tailor, and at No. 12 Moses Cohen, curiosity dealer. The rate books for March 1849 for Charles Street: Name of occupier: Richard Dearie, House, rateable value £49, rate at 8 in the £, £1 12s 8d. Amount Collected £1 12s 8d. Richard was bankrupt by June 14th 1849 and the lease was sold at auction.

Photo: Claire Grey 2012

By 1850 the family were living at Guildhall Chambers, Basinghall Street in the City of London where they can be found on the 1851 census: Jessie aged 18, Maria aged 12, Annie aged 9 and John 3 months. There is no record of George. Bessie and Mary were at a boarding school in Croyden. Richard’s last son with Eliza was born in 1851 and was also named John, the Scottish tradition of using the grandfather’s name. Richard was unable to pay the rates (property taxes) and they moved from house to house, leaving debts behind them.

The family moved to 10 King Square where John died from whooping cough at the age of nine months in September 1851.

By November 1851 Richard’s bankruptcy was announced in the London Times. He had debts of £1,487. They moved to 115 Nichols Square in 1852. In 1853 his father John died suddenly aged 81. John had property in Glasgow and Richard was the eldest son.

It is not known when Eliza, Richard's wife died, the family story has it that she died of drink and in poverty. By this time perhaps she was ill or afraid to have any more children who might die. Richard was possibly drinking as well, since his job gave him easy access to alcohol. By April of 1854 he had a sexual relationship with his stepdaughter Jessie Smart who gave birth to his son, also called John, on 16 January 1855. We do not know the nature of this relationship. We don’t know yet where the family or different parts of it lived immediately after they left Nichols Square.

Right: Nichols Square photograph from the City of London, London Metropolitan Archives. Permission for use agreed.

In 1844 when Richard and Eliza were back in London his occupation was described as Gentleman. They stayed with Eliza’s family in Chiswick where her mother ran a school. Eliza’s disgrace with Smart the sailor and her unmarried motherhood, seems to have been forgiven. They returned to America in 1845 but were back in England by 1846. Eliza gave birth to two more boys, Archibald in 1846 at Warren Street who died at 5 months and John in 1850 at Guildhall Chambers, Basinghall Street , he only survived for 9 months. Richard began to work again as a wine merchant and customs house agent. They moved frequently. From Warren Street in 1846, to 8 St Swithin's Lane in 1848, where Richard was listed as a commission agent. Although this could have been a business address. By 1849 he acquired an Inn just north of Soho Square at 9 Charles Street called the Fish and Bell. But by June 1849 he was bankrupt, and the lease of the Inn was sold off at auction. In the same year his eldest son John by his first wife Margaret died in a steamship explosion.

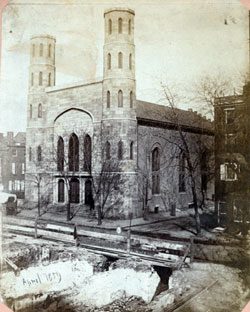

Right: St George's in Bloomsbury. London. Photographed by Claire Grey in 2011.

Marriage to Elizabeth Hogg and move to America.

Richard and Elizabeth married at St. Georges Church in Bloomsbury, London on 27 January 1838 using a special licence taken out the day before. This was expensive and usually used when people were about to go abroad or for confidentiality or when it took place in a parish where neither party lived. He was still living at Kings Road, Pentonville, while her address was given as the British Museum, Great Russell Street. She had been abandoned by her lover, Smart, a sailor, and been left with a child, Jessie then aged five. It only took one of the new steam ships 26 days to cross the Atlantic; they left England for America and settled in Philadelphia. Richard and Eliza had at least six children in America: Maria, born on 22 October 1838 and baptised at St Stephens' Church, Philadelphia on 13 November, Elizabeth born on 19 July 1840 and baptised at St Stephen's on 29 October. She must have died young. George was born in 1841, Annie in 1842 in New York, Bessie in Pennsylvania in 1843, and Mary in New York in 1845. Eliza returned to England in 1844 for the birth of Donald in Chiswick but he only survived for 4 days. Family history says that the whole family ate together: six from his first marriage and eight from the second. However it is more likely that the children of Margaret Watt were brought up her relations in New Orleans, which is where they lived.